By Ned Lazaro and Barbara Mathews

Massachusetts residents, in company with European colonists throughout colonial North America, enslaved, purchased, and sold Native American and African American people. Enslaved men, women, and children were common sights in fields, shops and houses, including Deerfield; 38% of households on the town’s mile-long village street included at least one enslaved person by the mid-1700s.

Enslavers regularly placed “Run Away” advertisements in 18th-century American newspapers when their human “property” attempted to escape a life of perpetual bondage. Such ads are a powerful tool for present-day researchers documenting resistance to slavery. They also offer glimpses of individual enslaved people as they appeared to white contemporaries. Despite their inherent bias, run-away ads are thus an important source that can help us to better understand the clothing and appearance of historically under-represented people living in 18th-century New England.

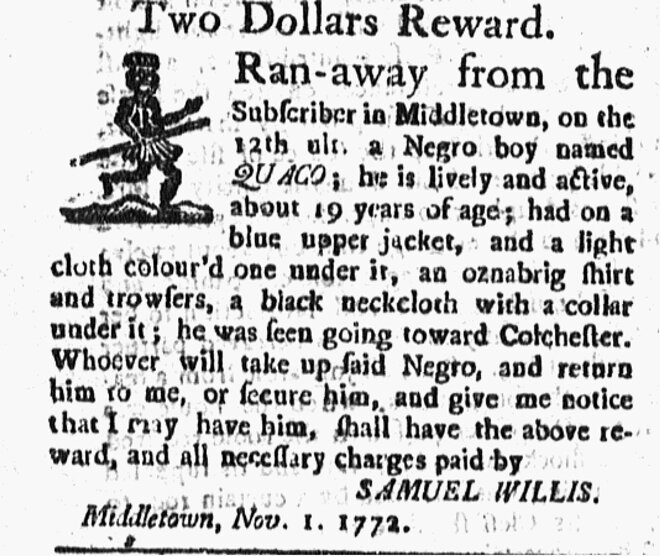

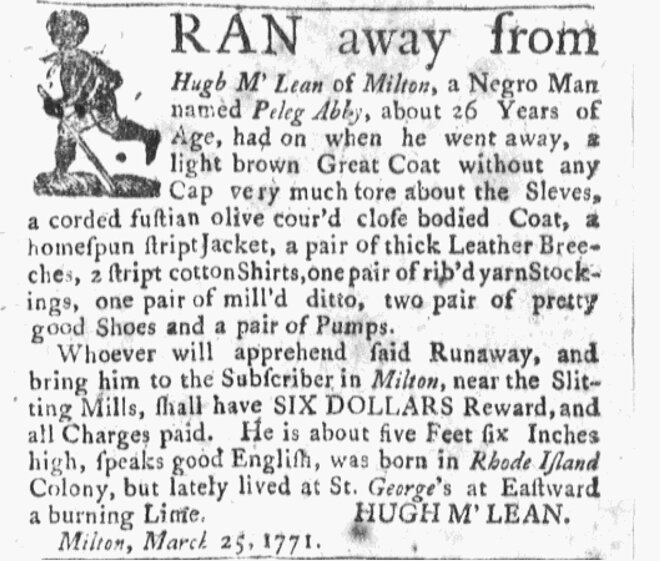

These formulaic advertisements, which appear in newspapers in New England and elsewhere throughout the 18th century, appear at first glance to be straightforward announcements. They often begin with the promise of a reward for the return of an escaped enslaved person, usually identified only by a first name. Descriptions of physical characteristics and character traits came next. Frequently, an ad shared with readers the last known location or planned travel route, if known, or surmised, if not.

Slave owners paid for the ads themselves and frequently paid an additional charge to publish them in multiple editions of one or more local newspapers. This suggests that the slaveholder expected their audience was literate, but not necessarily reading every issue of the paper regularly. A notice from John Lloyd of Stamford, Connecticut, seeking the capture and return of an enslaved manservant named Cyrus in 1761, confirms that advertisements also had a life beyond the specific issue(s) in which they appeared:

“As inserting the Advertisements in the several News-Papers is judged the most expeditious Method of spreading them far and near, if any Gentleman will be so good when they have read their Papers to cut out the Advertisement and set it up in the most public place, it will be esteem’d as a Favour.”[1]

For 21st-century readers, these announcements are far more complex. Written from the point of view of the enslaver, they were meant to be read and acted upon by a white, presumably sympathetic readership. The text thus contained inherent biases and accompanying shared meanings among whites and slaveholders regarding enslaved people and people of color in general. While garment descriptions themselves might be objective in some respects (a petticoat is a petticoat, understood by all classes in society), descriptors of other visual aspects of appearance sometimes employed qualifiers that were negative.

The visual descriptions of run-aways are thus an important, albeit biased, source for gaining more knowledge about the appearance of enslaved individuals. The ads overwhelmingly describe visual characteristics, chief among them clothing. Historian Rebecca Fifield notes the importance of these ads to help reconstruct the clothing of non-elite females in the eighteenth century; the same can also apply to run-away men.[2] Frequently, the clothing listed suggested practical, unfashionable clothing made from coarser textiles that rarely survive in museum collections today. A nineteen-year-old man named Piggen ran away in New London, Connecticut, in 1773 wearing “a woolen shirt checkered black and white, an inside jacket of the same Colour, a motley coloured outside jacket, a pair of double soled shoes, and an old felt hat.”[3] These ads also help give a sense of the reuse of clothing for the enslaved. Eighteen-year-old Jack ran away in 1776 wearing “a red mill baize jacket, the sleeves newer than the body,” revealing how worn-out parts of garments worn by poorer classes could be remade, for less money, rather than newer garments commissioned.[4]

Some enslaved persons wore comparatively better clothing, which may reflect either their position in a household, what they hoped to sell, or both. A “Negro Man Servant named CROMARTE, commonly called CRUM,” ran away from Samuel Fitch of Boston wearing “an old Hat” but also “a good grey Frock [coat] of Beaver Coating,” a red cloth short waistcoat double breasted…three white linen shirts ruffled at the bosom…a pair of Buckskin Buff-colour’d Breeches almost new” along with other items.[5] A young man named Robin ran away wearing “a red Plush jacket and …small, round Silver Buckles in his Shoes” along with taking away “a green flower’d Russel Banyan.”[6] Other enslaved men had wigs[7], knit breeches[8], and “pretty good pumps.”[9] Regardless of the clothing they wore, run-away enslaved persons could not easily hide their status. Cyrus escaped from John Lloyd still wearing “an old iron collar riveted round his Neck and a Chain fastened to it” beneath his clothes,[10] similar to Quaco, a nineteen year-old man who still wore (because he could not remove it himself) a slave collar underneath his black neckcloth.[11]

Garment descriptions are usually organized (to the best of the owner’s memory and ability) in two ways; what the runaway was actually wearing, and the clothing they took with them, possibly as a change of clothes or to sell to earn income for travel, food, or lodging. Both the quality and quantity of clothing run-aways took with them varied considerably. H.H. Post’s ad seeking the return of an enslaved fifteen-year-old boy named Shute remarked that the only clothing the boy took with him was what he wore; a blue jacket and striped trousers.[12] Whether that was indeed all that the run-away had or if they were the most visible aspects his owner could recall is unknown. Such meager clothing contrasts with an earlier advertisement in the 1760s from Rhode Island, in which an enslaved man named Ben not only wore “a Thunder and Lightning Woollen Coat, a double breasted striped flannel jacket, a Tow Shirt, and Worsted Stockings,” but also “carried off two Pair of Shoes, one Pair new, and the other old…a Bundle of Cloaths [sic], consisting of Tow Shirts, and a Check Shirt, with other Things unknown.”[13] Extra clothing might have been taken by a run-away for either a change of clothes to make apprehension based on description of their dress more difficult, or possibly to sell within the second-hand clothing trade.

Since run-aways were considered property, they were frequently described in language and a depth that would rarely be used among whites to directly describe each other.[14] Hair, complexion, height, identifying scars, and other features considered abnormal by a white audience, or noteworthy enough to make the runaway stand out, often accompanied the descriptions of clothing. For example, a “Man-Slave named Ben” who ran away from Jonathan Hazard, Esq. in South Kingstown, Rhode Island, was described as having “a remarkable gray spot of Hair on the back part of his Head, and several Scars about his Wrists.”[15] Slave owners placing the ads often ignored a whole range of skin tones, often distilling complexions down to “very black”[16], “not very black,”[17] and “yellow,”[18] among others. Hair of non-white run-aways, too, was often described disparagingly, such as a reference to hair that was “wool…combed in taste.”[19]

Other nuances of a run-away’s ethnicity were ignored or unknown by many of the owners who placed ads. Many of the runaways were described in simple terms that suggested their skin color was other than white. In the runaway ad he posted in 1761, John Lloyd described Cyrus as having the ability to “speak good English, and a little French,” possibly suggesting a Creole or West Indies background or experience.[20] Step, a twenty-seven-year-old enslaved man who ran away in Boston was described as “a stout Molatto.”[21] Crude, simplistic graphics accompanying some runaway ads in the 1770s and early 1780s in Massachusetts and Connecticut reinforced such either-or dichotomies, depicting black figures literally running, dressed in either draped skirts and crowned headwear and carrying a spear as seen in the above ad, or else in European style clothing and a walking stick, such as this advertisement for Peleg Abby, below.[22]

The advertisements reveal other, non-visual aspects of an enslaved individual’s visual identity. Speech was one such descriptor. Shute, a fifteen-year-old enslaved boy who ran away in 1792, was noted as “speaking Dutch, and some English, tho’ badly.”[23] Character was sometimes referenced, usually pejoratively. A “Negro Man Servant” named Prince was described by his owner as pretending to be both religious, and free,[24] while a man named Bridgwater is “well known…not for his Honesty.”[25]

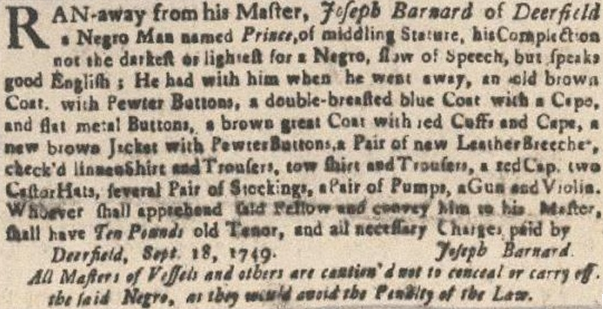

While newspapers were frequently published in larger cities such as Boston and Hartford, those placing advertisements often came from the surrounding urban and rural communities. Deerfield resident Joseph Barnard placed just such an ad in the October 2, 1749 issue of The Boston Weekly Post-Boy, below.

The Boston Weekly Post-Boy newspaper, October 2, 1749. Collections of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association

Barnard sought to recover Prince, an African American man who had escaped from Barnard’s control the previous month. In addition to briefly describing Prince’s person and demeanor, Barnard informed readers about the clothing and other articles Prince “had with him when he went away.” According to Barnard, Prince made his escape carrying a variety of items that included three coats, two hats, several pairs of stockings, a gun and a violin. Assuming this was an accurate list, there may have been garments Prince physically wore as well as clothing he packed for his escape. A change of clothing might have helped him flee pursuers. The additional clothing would also have had resale value in the thriving used garment trade. The sale of such extra clothing, combined with playing the fiddle, might have been a way for him to earn money to begin a new life. This run-away ad and a handful of account book entries are all we know of Prince, and include the sad knowledge that his attempt to escape a life of servitude did not succeed. By 1750 he was once again under Joseph Barnard’s control. Two years later, Barnard recorded paying two shillings for “a coffin for Prince.”

A quarter century after Prince’s death, the inherent contradictions between perpetual bondage and the American Revolution’s promises of individual freedom and inalienable rights put chattel slavery on the defensive throughout the new United States. It nonetheless flourished in the South until the Civil War and persisted in Massachusetts until the end of the 18th century; carefully crafted gradual emancipation laws ensured the continued presence of enslaved people in southern New England, New York and other northern states well into the nineteenth century.

[Transcript of Prince ad:]

RAN-away from his Master, Joseph Barnard of Deerfield

a Negro Man named Prince, of middling Stature, his Complection

not the darkest or lightest for a Negro, slow of Speech, but speaks

good English; He had with him when he went away, an old brown

Coat. with Pewter Buttons, a double-breasted blue Coat with a Cape,

and flat metal Buttons, a brown great Coat with red Cuffs and Cape, a

new brown Jacket with Pewter Buttons, a Pair of new Leather Breeches,

check’d linnen Shirt and Trousers, tow shirt and Trousers, a red Cap, two

Castor Hats, several Pair of Stockings, a Pair of Pumps, a Gun and Violin.

Whoever shall apprehend said Fellow and convey him to his Master,

shall have Ten Pounds old Tenor, and all necessary Charges paid by

Deerfield, Sept. 18, 1749. Joseph Barnard

All Masters of Vessels and others are caution’d not to conceal or carry off

the said Negro, as they would avoid the Penalty of the Law.

[1] Green & Russell’s BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, October 19, 1761: 3.

[2] See Rebecca Fifield, “Runaway! Recapturing Information about Working Women’s Dress through Runaway Advertisement Analysis, 1750-90

https://www.readex.com/readex-report/runaway-recapturing-information-about-working-womens-dress-through-runaway, accessed July 30, 2020.

[3] The Norwich Packet and the Connecticut, Massachusetts, New-Hampshire, and Rhode-Island Weekly Advertiser, December 16, 1773, 4.

[4] The New England Chronicle, May 9, 1776, 2.

[5] The Massachusetts Gazette, AND THE Boston POST-BOY and ADVERTISER, November 15, 1771, 4.

[6] THE Boston Gazette, AND COUNTRY JOURNAL, May 1, 1769, 4.

[7] The BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, January 4, 1768, 4.

[8] The BOSTON Evening-Post, March 23, 1767, 3.

[9] The BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, Oct. 8, 1764, 4.

[10] Green & Russell’s BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, October 19, 1761: 3.

[11] The NEW-LONDON GAZETTE, November 13, 1772, 4.

[12] The Columbian Centinel Extra, November 7, 1792, 3.

[13] THE NEWPORT MERCURY, August 19, 1765, 3.

[14] Jonathan Prude, “To Look Upon the ‘Lower Sort’: Runaway Ads and the Appearance of Unfree Laborers in America, 1750-1800.” The Journal of American History, Vol. 78, No. 1 (June 1991): 134.

[15] THE NEWPORT MERCURY, August 19, 1765, 3.

[16] THE WESTERN STAR (Stockbridge, Massachusetts), May 8, 1797: 4.

[17] Green & Russell’s BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, February 11, 1760: 3.

[18] THE Boston-Gazette, AND COUNTRY JOURNAL, May 1, 1769: 4.

[19] The New England Chronicle, May 9, 1776, 2. For more information on white biases of the hair of enslaved people, see Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 61, No. 1 (February 1995): 45-76.

[20] Green & Russell’s BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, October 19, 1761, 3.

[21] The BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, January 4, 1768, 4.

[22] See for example The Massachusetts Gazette, and the Boston POST-BOY and ADVERTISER, March 25, 1771, 3; The NEW-LONDON GAZETTE, May 28, 1773, 3; THE CONNECTICUT GAZETTE; AND THE UNIVERSAL INTELLIGENCER, August 17, 1781, 4.

[23] The Columbian Centinel Extra, November 7, 1792, 3.

[24] Green & Russell’s BOSTON Post-Boy & Advertiser, November 29, 1762, 4.

[25] THE BOSTON Weekly Post-Boy, December 2, 1745, 2.