When did we become the United States? Most Americans who know something of our history would probably say 1776; others might mention the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention in September of that year. And what of the rest of the world? When did widespread recognition of our sovereignty occur? Far less certainty surrounds that date, if a single one can be ascribed at all. A good guess would be sometime after the conclusion of the War of Independence with Britain. In terms of our then-adversary, British material culture offers a clue.

George Washington and Benjamin Franklin achieved international repute as military and diplomatic leaders for the American cause. This renown only increased following the surrender of Cornwallis to Washington at Yorktown, Virginia, in November 1781, which led to complicated peace negotiations the following April. With Franklin acting as Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States, preliminary articles of peace had been created by November 1782, with a final treaty with Britain signed in Paris in September 1783.

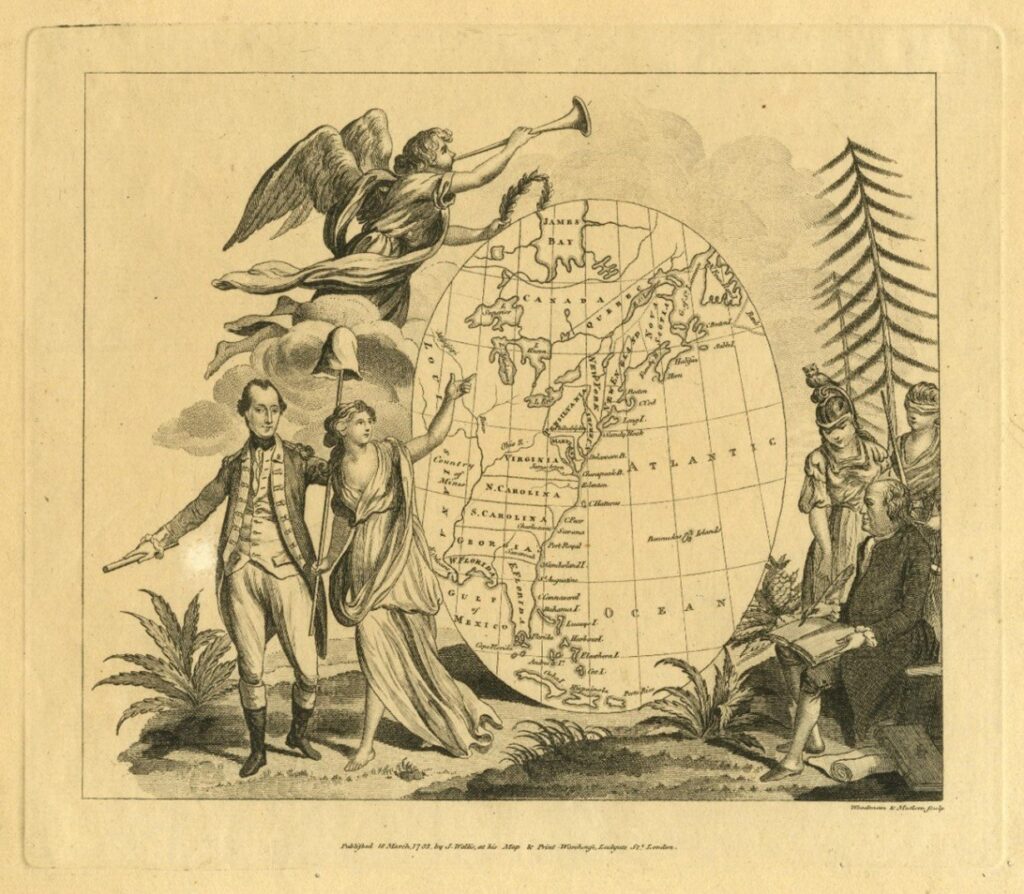

Images of Washington and Franklin had circulated before the war’s end, but peace brought forth new opportunities for recognition and adulation.[1] Most depicted the men separately, but a few combined the two. A recent gift to Historic Deerfield is an example of the pairing of these heroes of the Revolution that provides a glimpse into the life cycle of visual culture. The museum received a framed and matted grisaille (gray monochrome) watercolor, measuring 6 x 7.5 inches, which depicts Benjamin Franklin and George Washington in an allegorical scene. [2] On the left, Franklin is instructed in his writing by Minerva, goddess of wisdom, with blindfolded Justice standing nearby.[3] Opposite, Washington gazes at the viewer while escorting the figure of Liberty, who gestures toward the new country. Above all, the winged figure of Fame holding a laurel wreath heralds the allegorical scene with a trumpet blast.

In the center of the image an oval map of the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to Florida has been pasted down. Drawn in brown ink on different paper than that of the watercolor, the map depicts the United States, with state names and boundaries labeled. Two small portions of the map have been cut away to allow the underlying, and possibly earlier, watercolor image to be seen. The visual style of the map contrasts with that of the watercolor, indicating two different hands. Although the item has been removed from its frame and mat, no further information is revealed on the verso.

The watercolor/drawing appears to be the original design for an untitled print in the British Museum (1865,0610.1143).[4] John Wallis (1745-1818), who sold maps, prints, books, and games at his “Geographical Warehouse” in Ludgate, London, published the print on March 18, 1783. The print’s engravers and printers, Henry Mutlow (1756-1826) and Thomas Jones Woodman (1758-1817), directly copied the vignette from the original, causing Franklin and Washington to switch positions when printed.[5] However, they engraved the map in reverse so that the printed image reads correctly, suggesting that the engraver intentionally re-arranged the figures. Less noticeable are the map’s extra place names (e.g., the Great Lakes, New Orleans) and addition of Caribbean islands not found on the original drawing. The print’s rarity raises questions about its intended audience and purpose. No advertisement for it has yet been located, and speculation on the British Museum website of its possible use as a frontispiece remains unsubstantiated.

A hand-drawn statement later added to the watercolor’s mat names Richard Woodman as the maker (“fecit.”). This would refer to Richard Woodman the Elder, as his more famous son – also an engraver/artist of the same name – was not born until 1784. The senior Richard Woodman apprenticed with Thomas Jones Woodman in 1781 and may have been confused with his master, Thomas, by the creator of the attribution cartouche. The source of Woodman’s credit remains unknown, as does the apprentice’s involvement, if any, in designing the allegory.

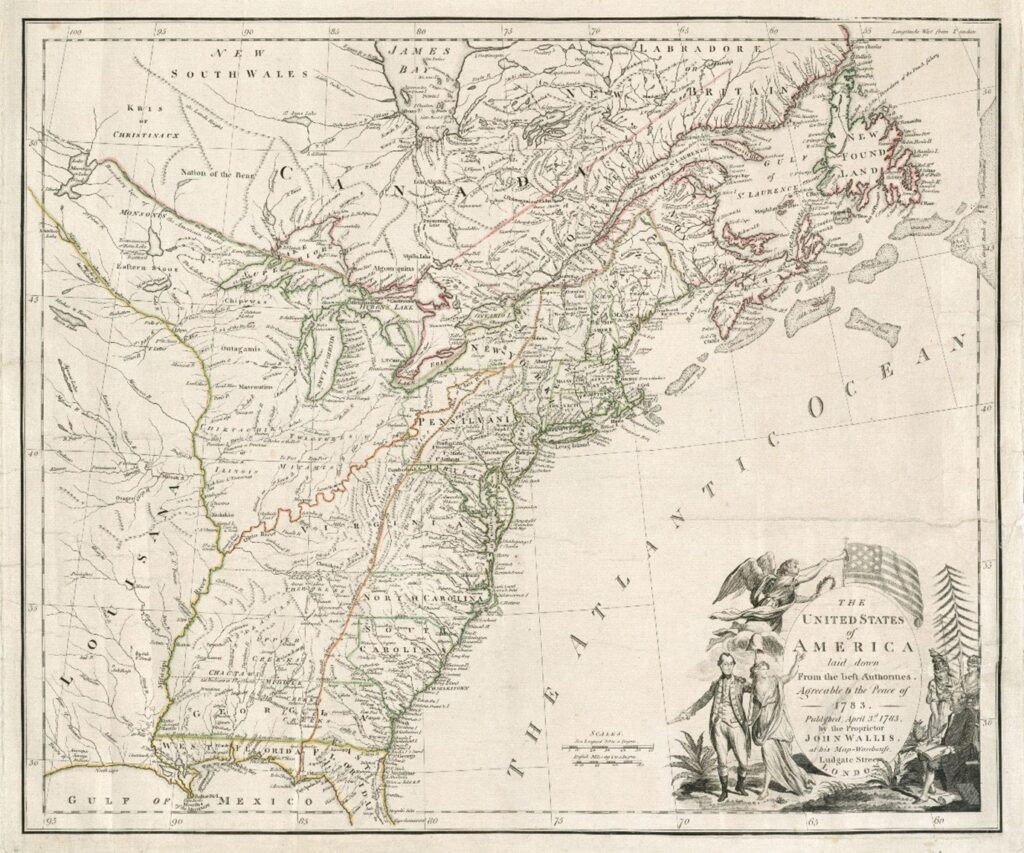

Less than a month after the print appeared, John Wallis published The United States of America, laid down From the best Authorities. With its geography derived from earlier printed sources, the map’s decorative cartouche is of particular note.[6] While retaining the orientation of the allegorical vignette of the British Museum print, a title replaces the oval inset of the eastern seaboard. Above this appears the American flag, making it the first printed English map to portray the ‘stars and stripes.’

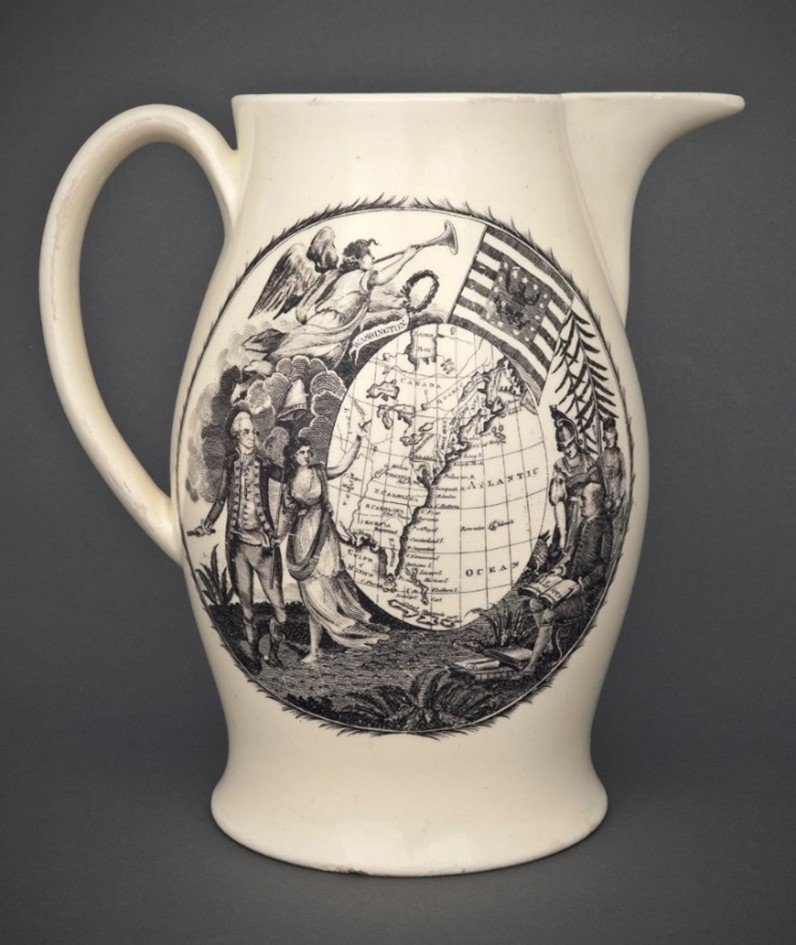

Design ideas freely circulated among craftsmen and frequently migrated from media to media. Enamellers of English transfer printed creamware soon appropriated the Wallis design and added it to jugs and other wares intended for the domestic and American markets. The ceramic design closely follows the small print by including the inset map. It departs from it by turning Washington’s face away from the viewer and toward the map and adding a banner with Washington’s name (but not Franklin’s) clutched by Fame. The unknown transfer-print engraver has added a faulty rendering of the American flag that centers the field, substitutes daubs for stars, and indicates 15 rather than 13 states. These differences in the flag and the use of the small oval map argue for the print, rather than the title cartouche of Wallis’ map of the United States, as being the jug’s design source.

Imagery celebrating American independence became commonplace after the war as British manufacturers eagerly sought to reestablish the lucrative American market. A decorative visual vocabulary featuring the figure of Liberty, the flag, and American heroes began to populate the era’s material culture. Thanks to the generosity of the donor who gave the grisaille watercolor to Historic Deerfield, we now know more about one influential design.