by James Golden, Director of Museum Education & Interpretation

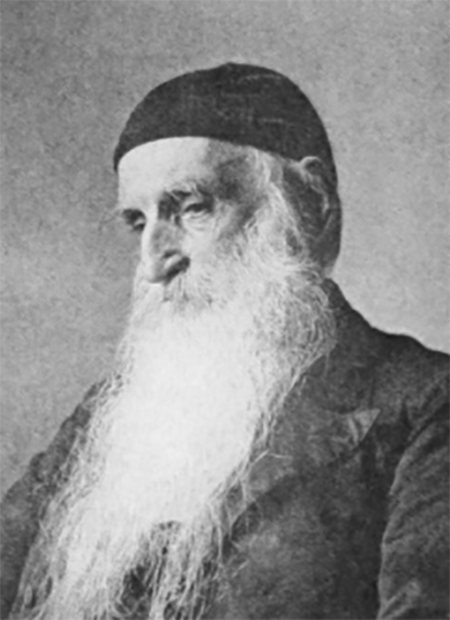

In 1896, Deerfield historian George Sheldon (1818 –1916), while reflecting on the hyper-partisanship noted in Deerfield resident David Hoyt, Jr.’s letters of an earlier time, wryly commented, “Before me lies a letter written in one of those periods, familiar to old men: ‘A crisis in the affairs of the country.’ We smile as we read the customary statement that, ‘on the result of this election, as on that of no other since the government was founded, does the life of the nation depend.’” Hoyt’s letter went on to elaborate that “the Indefatigable Industry of [the Democratic-Republicans] is perhaps without a paralel (sic). Every Art is used to delude the People.” [1] The sense of panic, the vitriol, and the conviction that one’s political opponents are duplicitous tricksters may not feel that historic.

But Sheldon’s detachment and perspective about a sense of crisis is all the more interesting given that he published his history in 1896, one of the most hotly contested election years—when Republican William McKinley defeated the Populist Democrat William Jennings Bryan over the issue of the gold standard. Born in 1818, Sheldon was 78 years old and had lived through twenty different presidential elections at that point. Unpacking his analysis helps us to see that incivility and hyperbole are not new to electoral politics, nor is a sense of crisis in American politics. Indeed, the word “crisis” rebounds throughout American political history, from the Nullification Crisis of the early 1830s to the Cuban Missile Crisis of the 1960s.

Sheldon was born during the so-called Era of Good Feelings, the period that followed the end of the War of 1812. Between 1796 and 1816 the pro-business New England-dominated Federalist Party had vied with the agrarian and Southern Democratic-Republican party. Following the American victory in 1815, the anti-war Federalists collapsed, and no rival emerged to challenge Democratic-Republican supremacy. While elections occurred, there was little meaningful opposition. That era of relative unity and lack of dissension was Sheldon’s childhood.

In his adulthood after the Civil War, the Gilded Age saw unprecedented hostility and political engagement: electoral turnout averaged 75 percent nationally and even reached 90 percent in certain states. Highly partisan newspapers emerged, dedicated not so much to accurate reporting as castigating the other side. Political machines, modern election managers and strategists, and a constant sense that the very soul of the country was up for grabs in every election pervaded the period. In another modern echo, one party had most of the Northeast, Midwest, and West as a lock while the other controlled the South. All elections hung on a few states. Then called the “doubtful states,” they were essentially what are now called swing states. Noting these trends, historian Charles W. Calhoun has traced a generational shift away from the politics of the Civil War and towards serious economic debates. [2] This culminated in the epochal 1896 election over issues of deep economic policy, when our own George Sheldon commented on the litany of electoral crises.