By Elyse Moore, Museum Guide and Hearth Cook

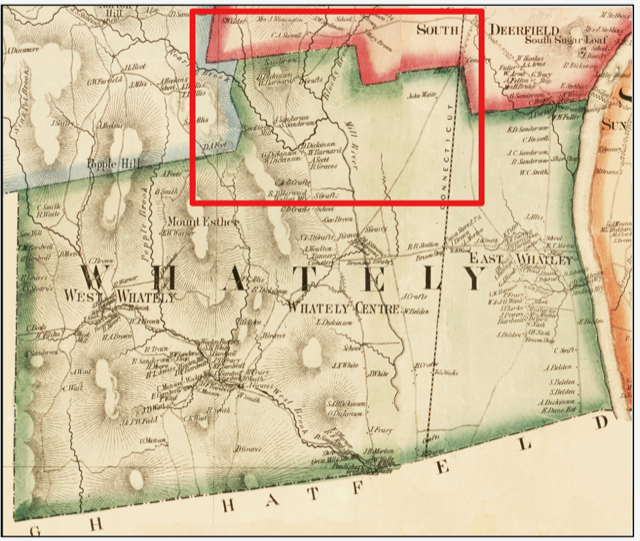

In the winter and early spring months of 1874 and 1876, Martha “Mattie” Ann Sanderson (1854-1933) and her mother, Abby H. Rice Sanderson (1829-1902), kept a journal of their work schedules, domestic cookery, farm production and inventories, sewing projects, daily weather reports, church and prayer meeting attendance and numerous other tasks, lessons, and interests from life on Elon and Abby Sanderson’s West Whately farm and in their rural Connecticut Valley community. Their farm, north of the town center where Dickinson Hill and Whately Glen are divided by the Roaring Brook, is part of a historical complex of Sanderson family farms still operating in Whately today, now in its ninth generation of family ownership.

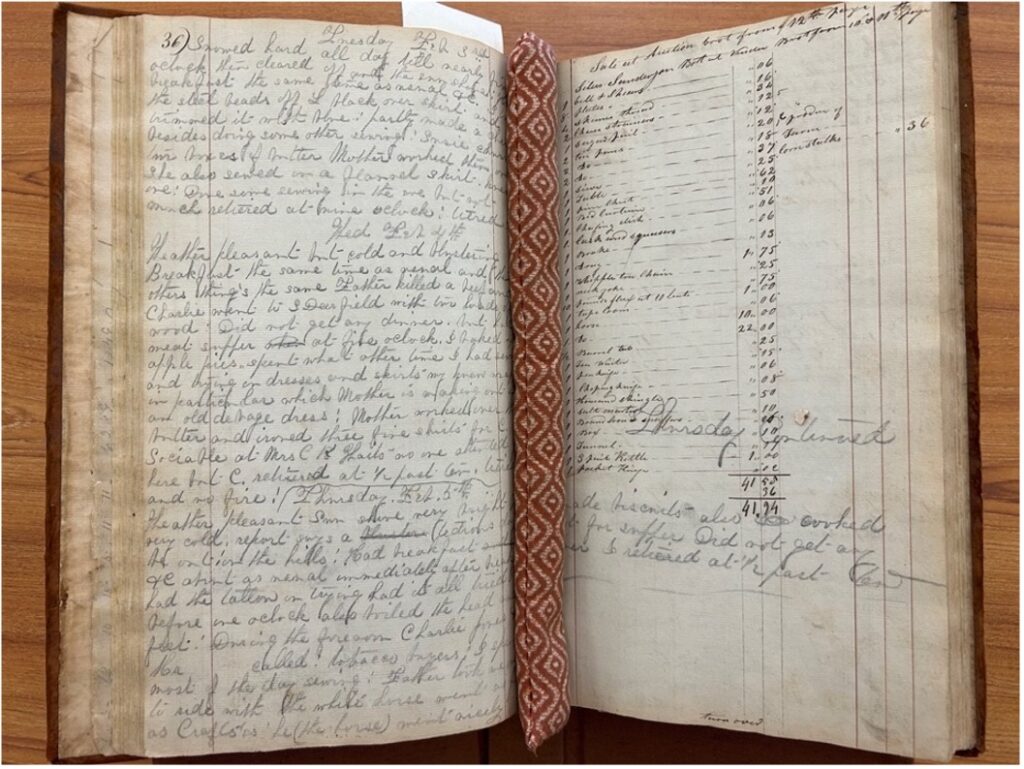

Abby’s and Mattie’s separate diary entries were discovered on some of the unused pages of an earlier Sanderson farm and logging business account book, one of four Sanderson family account books in the collection of the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association (PVMA) Library that details four generations of family, farm, business, and probate records between 1769 and 1876. The book that includes the diaries also details the extensive probate inventory of prominent family patriarch, Deacon Thomas Sanderson, taken in the summer months following his death at the age of 78 in March 1824. The account books were likely passed down over two generations to Abby’s husband, Elon, Thomas’s grandson. Abby Sanderson and her daughter Mattie left their own account — daily diary entries and baking lists that covered several months during 1874, and two years later in 1876. Neither 1870s diarist mentions the previous purpose of the account book that later became their journal.

In addition to the two women’s diary entries, a small selection of nineteenth-century post-Civil War poetry—of Longfellow, Buchanan and others—is copied on page sequences in a handwriting style different than either diarist’s, alongside the diary entries—perhaps as an aid to memorization, perhaps as historical context to mark the passing of that conflict fought on far-off, yet still-significant battlefields. Younger children’s drawings, doodles, and simple diary entries suggest the occasional inclusion of other family members in the diary project. A young Georgie Sanderson records his own entry on the account book’s front endpaper, “Father and Charlie have let the sugar place. They have gathered 7 barrels of sap…” Maple sugar-making was regular early spring farm work for any farm with substantial acreage forested with the sugar maples so common to the Connecticut Valley region.

The Sanderson diaries’ detail of food production and preparation, textile production, healthcare, and community presence within family, religious, educational, and neighborhood networks opens a window into their farm and family history nestled within the pages of previous generations’ business records and probate accounts—as each generation passed its assets and reflections on to the next. The juxtaposition of Abby’s and Mattie’s work and life experiences with historical Sanderson farm and probate accounts provides a multilayered and generational interpretation that expands our understanding of rural western Massachusetts farming in the nineteenth century.

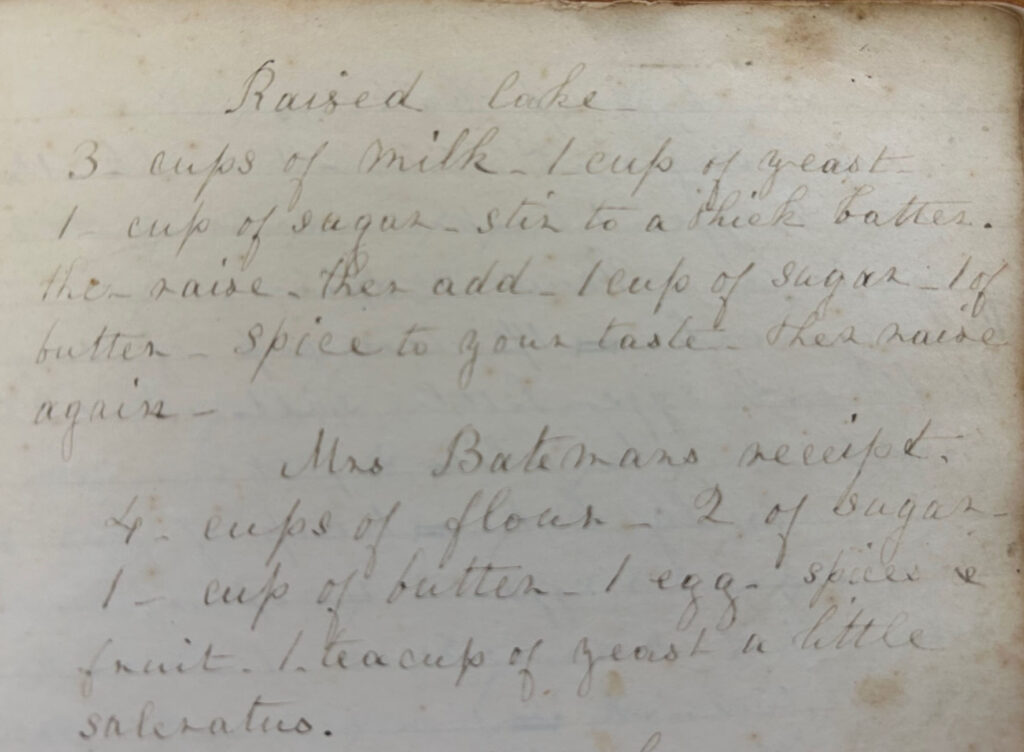

Mattie’s diary begins on January 10, 1874 with a one-word weather report—“Pleasant”—and continues with an account of the day’s baking: “baked one loaf of rye bread and one of wheat. Two loaves of raised cake.” Though she did not recount the recipes for the many breads, savory dishes, and desserts she made during the time she kept her diary, a manuscript recipe for Raised Cake in the 1877 receipt book of Celia Mann Kimball (1828-1910) of South Deerfield, seen in Figure 4, exemplifies a local interpretation of this popular late-nineteenth century cake recipe.

Manuscript receipt books like Mann Kimball’s in the Memorial Libraries’ two collections (Historic Deerfield and PVMA) now have a searchable recipe database—a user-friendly search tool for locating period recipes, like Raised Cake, within the scope of the collections. Also women’s magazines of the period, such as The Ladies Home Journal, and Godey’s Lady’s Book, regularly published popular recipes, such as Apple Shortbread, that might be otherwise unfamiliar to the twenty-first century kitchen. This post draws from the Memorial Libraries’ culinary database, as well as from those “women’s magazines” to illustrate a selection of recipes made in the Sanderson kitchen and served at the family table in the period between 1874 and 1876.

Mattie’s journal entries are indeed a record of her almost daily baking and family meal preparation responsibilities, in addition to the numerous other activities that filled her days and nights: church and prayer meeting attendance, dressmaking and cleaning, horseback riding and sleighing, maple sugaring, piano playing and singing, and attendance at occasional theatrical performances and lectures.

On January 19, 1874 Mattie wrote,

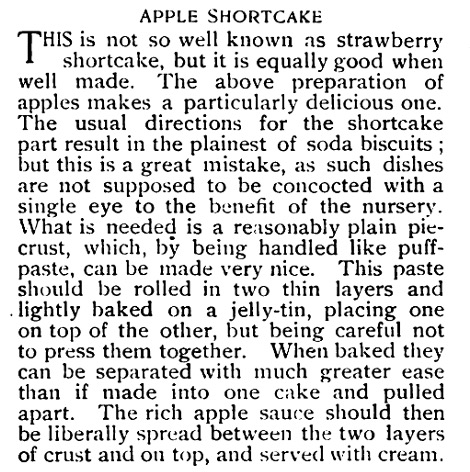

Made an apple shortcake for supper : Ironed most of the trimming on my black dress

The following late-19thc. narrative recipe published in The Ladies Home Journal, is only slightly less vague in its description of the preparation. Such is the case with many recipes of the period. Biscuits and “pastes” or pastry used for shortcakes would be recipes in regular family use, and need little or no additional reference. A family’s preferred pastry or cake might be made into a layered dessert filled with whatever fresh or preserved fruit was available. Four days later, Mattie remembered,

Picked over two barrels of apples and made some biscuits for supper.

By January, apples stored since the September or October harvest could be reaching the end of their usefulness and suggest the need to find apples sound enough to be used up in shortcakes, biscuits, or other simple fruit desserts. “Pick(ing) over” ensures that rotting apples, both unfit for consumption and a threat to those that still had some useful storage life, would be removed from storage bins and used up.

Mattie’s writing was not solely confined to a record of her work in the kitchen. In the following excerpt, she describes a Saturday evening outing in February to attend a concert in South Deerfield with her brother, Charlie and sister, Laura, and an Ashfield cousin, Asa Sanderson. Though her entry does not specify the mode of transportation, the time of year and the indication that each of the sisters “accompanied” the men separately, suggests that the group may have driven two horse-drawn sleighs nearly six miles each way over snow-covered dirt roads, from the Sanderson Farm high on Dickinson Hill in West Whately to South Deerfield Center—a lively and ambitious adventure on a mid-winter’s night.

Saturday Feb. 7th

… combed my hair changed my clothes &c. Did not sew but little : about four A.G.S. from Ashfield came: Had tea about five: and at ½ past six we all viz Charlie accompanied by Laura A.G.S. accompanied by myself started for So. Deerfield to attend a concert given by that comical Brown and his troupe: enjoyed it very much arrived home eleven…

Abby Rice Sanderson’s diary entries, beginning two years later on January 1, 1876, express a more sedate and businesslike tone. Her daily reports are typically less than half the length of her daughter’s memos. Like Mattie’s, her daily report begins with the weather.

Jan. 7th Friday

Weather is very cold – no snow at all – ground froze hard – Georgie more comfortable – baked – churned 2 boxes butter – men in tobacco – L & I did work – L took music lessons in afternoon (W.B. Russell Hatfield) Mrs. Crafts called in morning – Lizzie Sanderson Mrs. E Parker called in afternoon – Anna in evening – finished tobacco – had letter from Mattie – sat up till 5 AM then lay on lounge.

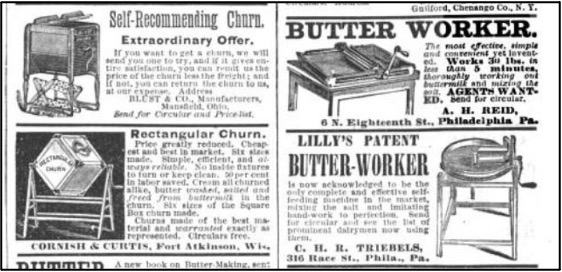

Like her daughter’s entries, Abby’s writings describe baking, sewing, and cleaning. But Abby’s work schedule also included weekly churning “ 1 to 2 boxes” of butter (15 to 30 pounds), followed within the next day or two by “ working over the butter.” Hand-made hardwood box churns, mounted on a frame with an attached crank handle, allowed the box to turn freely above the milk room floor—often for several hours—to achieve the separation of cream from the buttermilk and make it into butter. Though no image of the Sanderson churn exists in the historical record, box butter churns were typical of small-farm commercial butter production and were made in a range of sizes to accommodate the volume of milk suited to the individual farm. Churning butter by hand was hard physical work and was most often part of the women’s domain on a dairy farm.

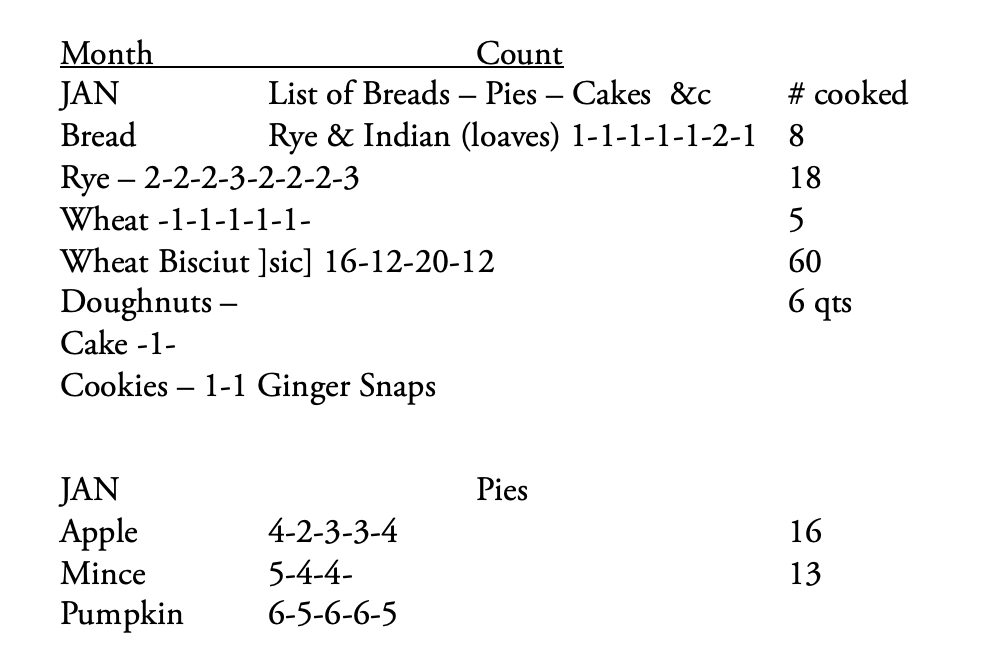

And Abby baked. Near the end of her journal, she kept a running chart of her baking production between January and April. Her baking entries show a businesslike approach not unlike the Sanderson account book entries of preceding generations.

Abby’s diary also included references to almost daily sewing or mending sessions, supervision of the work of outside help, extended sick-bed child care and doctor’s visits for her youngest child, Georgie, acknowledgements of the accomplishments of all her children, and the frequent entertaining of family and neighbors for dinner and tea. Neighbors, church acquaintances, and Sanderson relatives would “call” to visit and provide care and support in times of family illness and the heavy work associated with farm-animal slaughter for food, maple sugaring, and preserving the harvests. Or sometimes, friends and family would just arrive to pay a social call, stay for a meal, tea, or perhaps even an overnight. Abby’s return calls on her neighbors were less frequent than her entertaining them.

A religious connection to neighboring families is another primary feature of Abby’s diary entries. The Sanderson family’s regular attendance at Sunday morning and afternoon church meetings, supplemented with Wednesday and Friday prayer meetings, attests to the devout and contemplative nature of family life that accompanied daily work on the Sanderson farm. Regular references to visiting pastors and the scriptural themes of sermons and prayer meetings indicate the spiritual nature of Abby’s inner life.

The diaries detail a life with a perpetual work schedule whose days often ended “very, very tired,” at midnight or later. But there were other interests: education, music, extended family gatherings, and occasional social outings. Both Laura and Mattie took the train from Whately Depot to Springfield and Greenfield, respectively, for educational pursuits. Abby writes of taking the train to Cheapside (on Greenfield’s southern border with Deerfield) to attend Mattie’s graduation exercises with Mrs. Abercrombie. More often, however, it was their brother Charles who took them to the train “with the wagon” and picked them up on return trips. There were piano lessons, and occasional nighttime entertainments at Sanderson Farm that included “apples, popcorn and nuts” and group singing.

Laura Sanderson went on to establish a career as a teacher. Mattie married Frank Ward, a regular visitor to the Sanderson farm in 1876. The sisters lived together in Indianapolis, Indiana at the close of their lives, in the city where Laura opened and operated the Sanderson Business College, a lifetime venture.

But like many other women’s diaries of the nineteenth century, the Sanderson diaries are notable as much for what is not written, as for the diaries’ record of daily life in the small farming town of Whately. The diaries are limited to the winter and early spring months in their respective years, suggesting a pace of farm life so demanding as spring planting and dairying seasons ramp up, and perhaps no time in the day to prioritize the luxury of the written word. The writing in the diaries is almost exclusively confined to the Whately Glen farm and South Deerfield, with a bit of regional train travel. No mention is made of the impact of the Civil War or the importance of the industrialization of the Connecticut Valley. There is no reference to newspaper or magazine reading. The only reference to politics is the moving of town meeting and Election Day to “the hills.” And there is nothing written of a previous generation’s use of the same 1824 account book that became the Sanderson women’s journal near the end of the nineteenth century. But the writing of two generations of Sanderson women in the early industrial period, when farms were still largely maintained by the physical labors of their landowners, provides this unique glimpse into the world of two women’s work on one Connecticut Valley farm.