By Jeanne Solensky, Librarian

A comparison of two bindings from a recent gift highlights changes in bookbinding technology over seven decades. My previous post showcased a rare colonial binding that featured gilt tooling in a very restrained, elegant design. By the 1840s, advances and changing tastes culminated in exuberant gold stamping in this title, telling a different story than a master binder working in a small shop, but rather one of many workers using machinery in an assembly line production to finish a greater number of books. [Fig.1]

The highly decorated book is Miss Lambert’s 1842 “Hand-Book of Needlework,” one of several titles written by her on the subject. Lambert remains a shadowy figure; although she was married at the time, she chose the rather unusual route of using her maiden name. In the book’s preface she stated she was “indebted to my husband for his assistance in some of the historical notices, and again for his permission in allowing my maiden name to appear on the title-page, as being that by which I am more generally recognised in my avocation.” Lambert’s book was more than a manual; it contains not only patterns for knitting, crocheting, netting, and beading, but also chapters on the history of and equipment for needlework. Lambert faced much competition in the needlework manual category in this antebellum period as more women in the rising middle class had time to pursue fancy embroidery work.

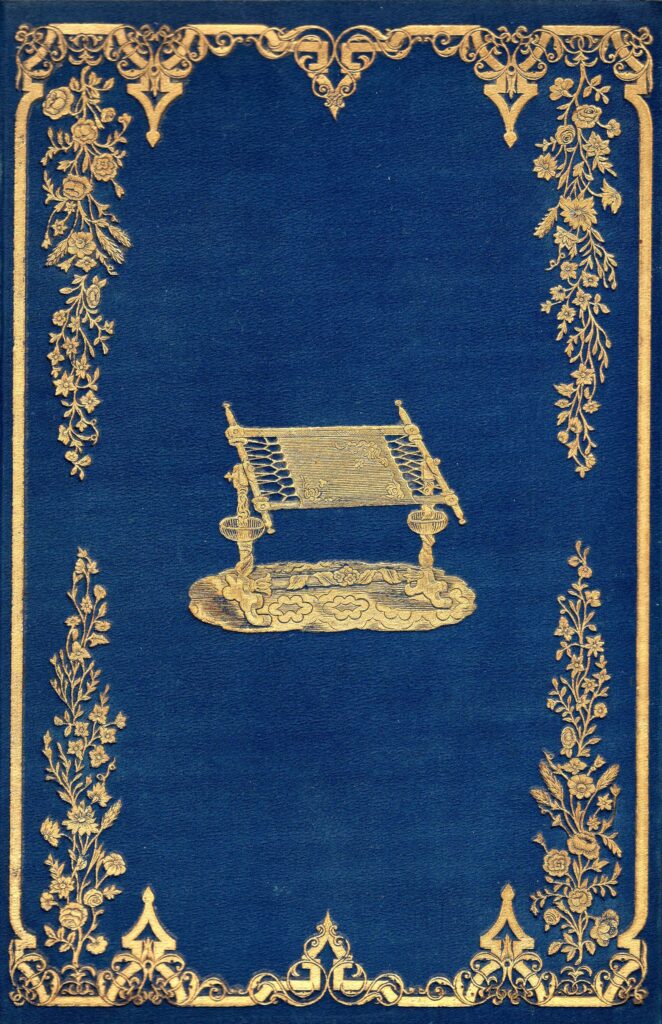

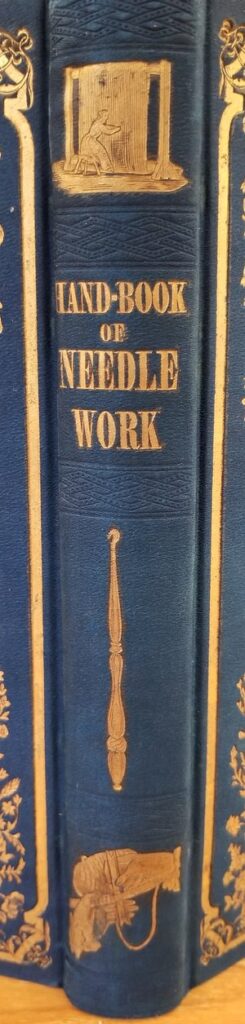

In an attempt to stand out in a crowded field, the publisher Wiley & Putnam contracted with a bindery to create an eye-catching design. The royal blue cloth on the book’s covers presented a contrasting background for an intricate floriated gilt border. A gilt vignette of an embroidery frame graces the center of both covers, with more pictorial stamps decorating the spine: a woman working on a tapestry on top, then a crochet needle placed lengthwise, with hands working netting needles at the bottom. While the title is also stamped in gold on the spine, the decorations render it nearly superfluous. [Fig. 2] Newspaper ads announcing the book noted the binding, calling it “splendidly bound,” and “elegantly bound in cloth.”

However remarkable the binding was, the binder was not identified in the book’s promotion; as noted in the earlier blog post, binders typically remained anonymous. Blind stamped on the bottom middle of the front cover for eagle eyes is “B. Bradley Binder Boston” as if he knew self-promotion was necessary. [Fig. 3] Benjamin Bradley of Boston established the first American bindery to specialize in cloth work in 1832, a relatively new process that was first experimented with in England in the 1820s. An alternative to expensive leather was sought, with binders first employing silk, satin, and other fabrics which proved too thin until later experiments with a starch-filled cotton cloth that stood up to adhesives were successful. This discovery, along with the development of a new casing process during the same period, led to a simplified, mechanized method that reigned supreme for over a century. Instead of books constructed with covers built directly on text blocks, covers of cloth case bindings were made as separate units and then attached to text blocks without sacrificing durability and allowing for more parts to be simultaneously produced. Decoration was no longer hand-tooled, but stamped and embossed onto covers and spines by machinery. The entire manufacturing process was faster, cheaper, and blingier than before. Bradley may have been concurrently running multiple stamping presses as this title was bound in a variety of colors besides blue; copies bound in green, purple, brown, and even a striped red cloth have been located in other library collections. [Fig.4] Besides working with celebrated Boston publishers Ticknor & Fields and Crosby & Nichols, Bradley was sought out by New York City publisher D. Appleton & Co.

Bradley may have stamped his name on books to advertise his business with no thought of long-lasting fame; fortunately his entrepreneurial acumen preserved a critical component of this book’s history. By harnessing the innovative power of technology, he and other binders democratized the book trade, bringing a greater availability of books – both useful and attractive – to expanded audiences.