by Nym Cooke

I was the lucky recipient of a Memorial Libraries Research Fellowship to study the musical activities of Deerfield resident Justin Hitchcock (1752–1822). Over seven three-day weeks in the halcyon Fall of 2024, I immersed myself in Hitchcockiana. During my time at the library, I pored over primary source documents, read chunks of various secondary sources, and went on “field trips”—to Memorial Hall Museum to see a pitchpipe and bass viol that Hitchcock is said to have played, to the Hitchcock house on Albany Road, and to Laurel Hill Cemetery to see Justin’s gravestone. The beauty of researching topics relating to Old Deerfield is that everything you need—a document, a historical object, a house, a graveyard, a knowledgeable person—is right there. Well, almost everything: my last field trip was to the Special Collections department of the Amherst College Library, where I spent some time with a music manuscript that figures importantly below.

I could single out many a nugget to represent the richness of my Deerfield fellowship! What stands out at this writing is my search for musical compositions that could be Hitchcock’s work. Justin makes numerous references to composing in his 87-page “Sort of Autobiography” at the PVMA Library. None of the handwritten tunes, anthems, and vocal parts in the 19 tunebooks at Deerfield—17 of them in the collection of the PVMA Library and two in the Henry N. Flynt Library—suggests the possibility of Hitchcock’s authorship. The music manuscript at the PVMA Library traditionally attributed to Hitchcock (probably on the basis of a pencil inscription, “Dea Justin Hitchcock,” inside the front cover) is a collection of fifteen secular songs, most of them vocal melodies with instrumental bass accompaniment, and none of them are traceable to Hitchcock. And there are two more convincing candidates other than Justin for the composer of the two pieces attributed to “Hitchcock” in the printed tunebook repertory: Miles Hitchcock, a correspondent of tunebook compiler and Andrew Law, or Reuben Hitchcock, a 1786 graduate of Yale.

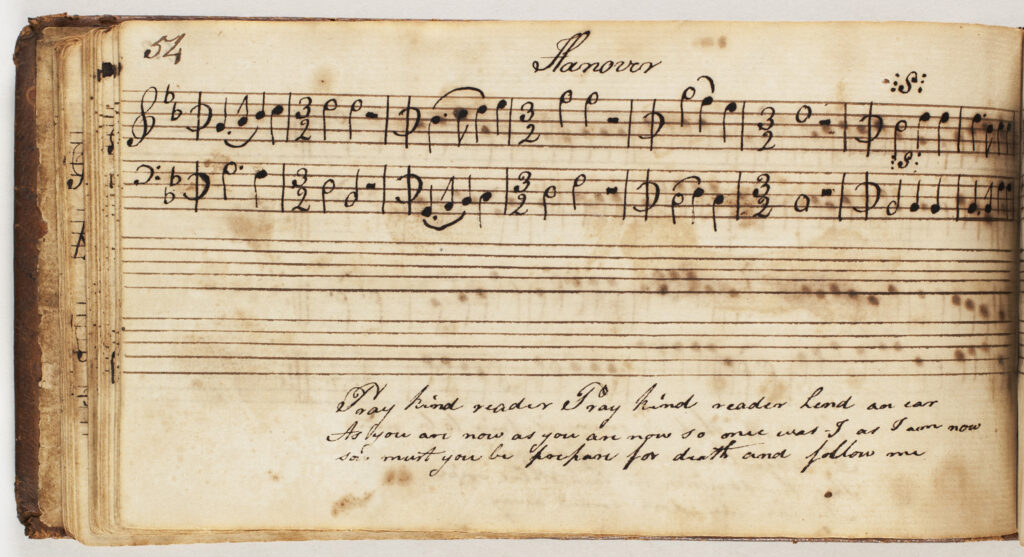

But there is one source that may possibly include tunes by Justin Hitchcock: a music manuscript at Amherst College which has inscribed inside its front cover, “Henry Hitchcock,s. / Deerfield April 25th 1805.” Henry, born 1783, was Justin’s eldest son. No other reference to Henry’s musical interests or abilities has surfaced, but this manuscript certainly suggests his active involvement in the sacred music of his day. Its 76 musical entries, a mix of four-voice settings, melody and bass pairs, melodies, and bass parts, exhibit a fairly wide stylistic range. Most of the four-voice entries are contemporary American tunes, while the two-voice settings found later in the book are older English pieces. There are a few chants, a couple pieces with secular texts, and three copies of Lowell Mason’s Missionary Hymn, which obviously postdate the “1805” inscription.

Five pieces in Henry’s copybook, all unattributed, are not included in Nicholas Temperley’s The Hymn Tune Index (Clarendon press, Oxford, 1998, and online), and therefore were likely not printed before 1821. Some or all of these could be Justin Hitchcock’s work, copied by Henry from his father’s manuscripts. And the text of one of these pieces, an eloquent two-voice plain tune titled “Hanover,” provides a definite connection to Deerfield, and thus speculatively to Hitchcock.

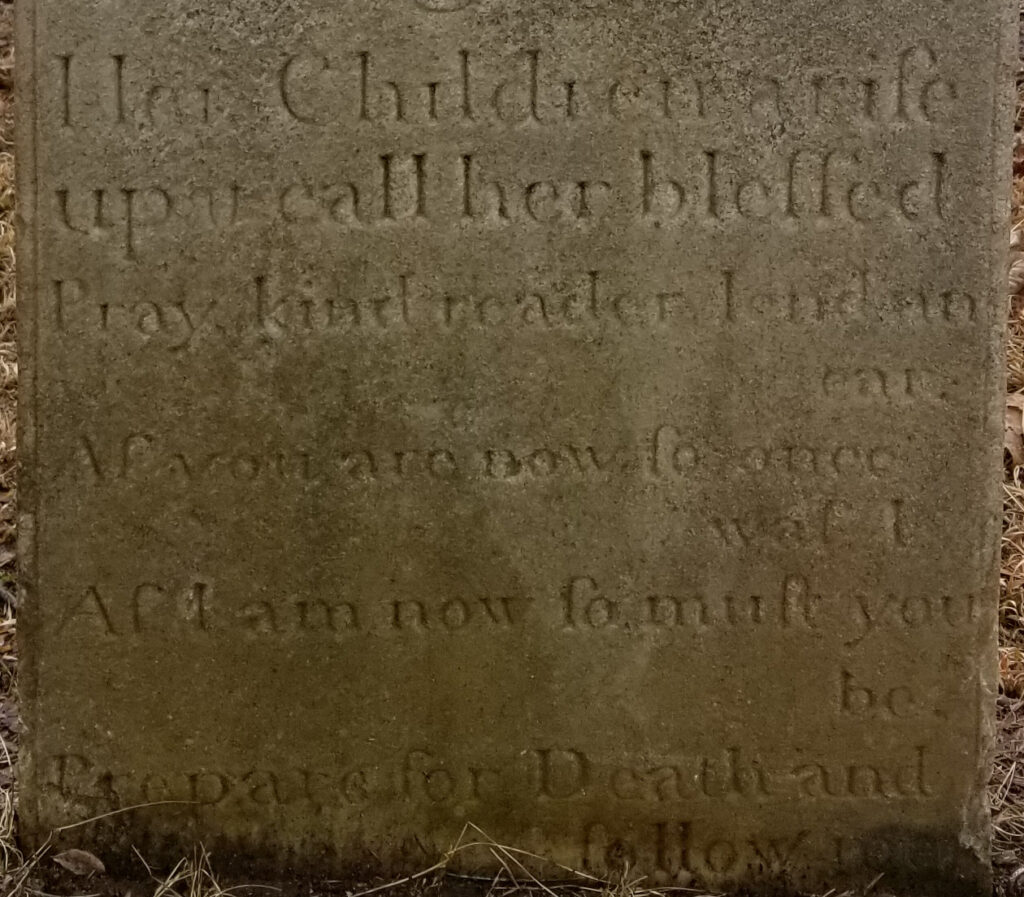

Hanover is a strong, eloquent setting of a text about mortality—a text which in various versions may be found on the slate gravestones of many a New England burial ground. There are no clumsy or unattractive harmonies, and both melody and bass project a sure sense of direction. The composer is clearly comfortable with changing the piece’s musical meter—six times—in order to accomplish his purpose in the first part of the tune: a call to the stone’s “kind reader” to “lend an ear.” The music’s three pauses (the silent third beats of its three measures in 3/2 time) seem to stop the passerby in their tracks, then command them to listen to what is coming—the all-too-familiar reminder that

As you are now, so once was I;

As I am now, so must you be;

Prepare for death and follow me.

The inevitability of mortal humans’ fate is underlined by the fourfold iteration of an insistent rhythm, on the words “you are now,” “once was I,” “I am now,” and “must you be.” Within its modest parameters, this is a thoroughly successful and poignantly expressive piece.

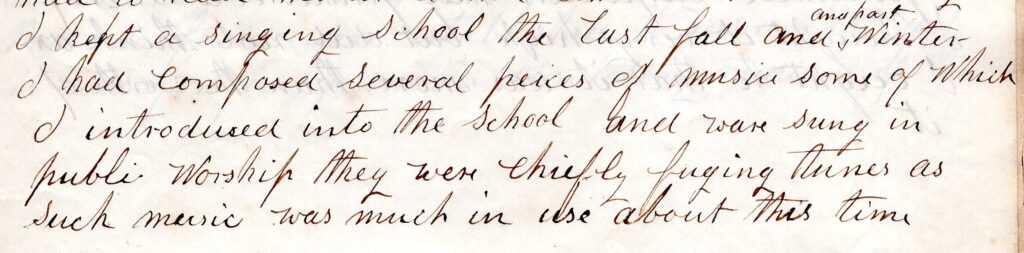

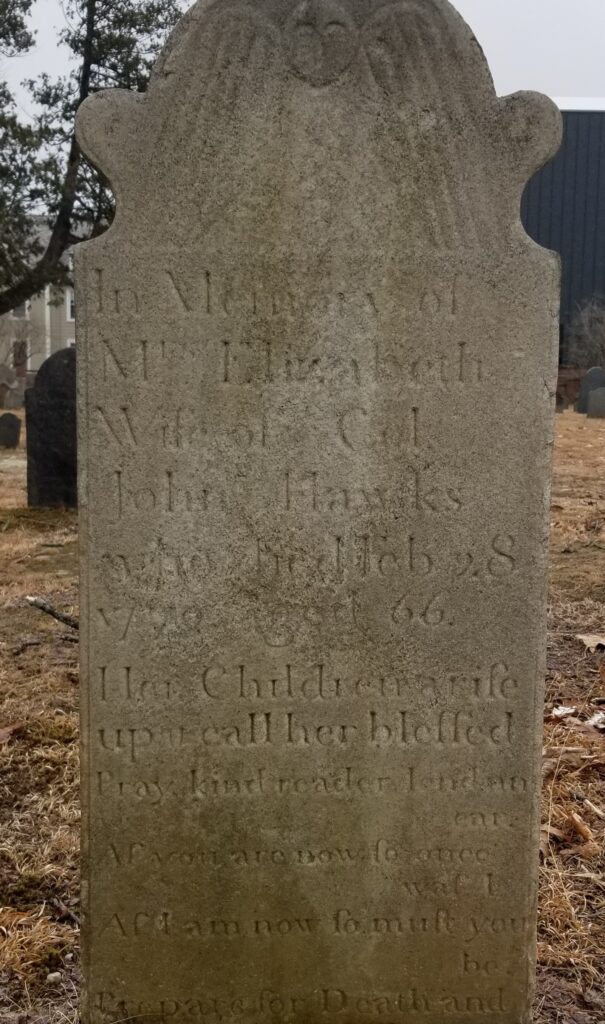

Beyond Hanover’s presence in the music copybook of Deerfield’s Henry Hitchcock, a further fact ties it squarely to the town. A thorough internet search reveals that the specific version of the text set by this tune, beginning with “Pray, kind reader, lend an ear,” has been located only on the tombstone of Elizabeth Hawks (née Nims) of Deerfield, who died on 28 February 1779 and is buried in the Old Deerfield Burying Ground—just down Albany Road from Justin Hitchcock’s house. At the time of Elizabeth Hawks’s death, Justin, who had joined the Deerfield church a couple of months earlier, was an established presence in town, known for his skills in music and orthography. He’d been teaching singing schools in the town for four years and was appointed Town Clerk for the first time in 1779. He was known by his fellow Deerfield residents as a composer; by his own account, as we’ve seen, at the time of his 1779–1780 Deerfield singing school he’d “composed several peices [sic] of music some of which I introdused [sic] into the school and ware [sic] sung in public Worship.” Moreover, there’s abundant evidence of various dealings that Hitchcock had with members of the Hawks and Nims families over the years. For example, Elizabeth’s great-nephew Zadock Hawks would attend the singing school Hitchcock taught in late 1792 and/or early 1793.

Given all this, it certainly seems natural to suppose that when Elizabeth Hawks died in early 1779 and the lines beginning with “Pray, kind reader, lend an ear” were carved on her tombstone, a member of the Hawks or Nims families asked young Justin Hitchcock to set those lines to music, and that Hitchcock’s setting eventually found its way into the music copybook of his eldest son.

Nym Cooke is an independent scholar with expertise in early American sacred music. Visit his website at: earlyamericansacredmusic.org.