By Allison Fulton

In the early decades of the 19th century, young white women at academies and seminaries across New England spent their days mastering foundational arithmetic, reading, and geography while also diligently learning the decorative arts to develop morals and artistic skills. One particularly important hub for the making and teaching of these ornamental arts was the Connecticut River Valley. Schools ran up and down the valley, including the Misses Pattens’ School in Hartford, CT; the Sarah Pierce School in Litchfield, CT; the Abby Wright School in South Hadley, MA; and the still operational Deerfield Academy that is nestled among the homes of Historic Deerfield.

The co-educational Deerfield Academy incorporated the ornamental arts into its curriculum for female students from its inception in 1799. Female instructors who had honed their own craft at schools like those previously mentioned brought their artistic skill to Academy classrooms, transferring “technique, style, and iconography across regions and generations.”[1] The transfers of craft technique via these multi-generational networks of white women are on full display at Historic Deerfield, whose museum and library collections contain many exceptional examples of ornamental art objects and arts instruction manuals that illustrate the techniques used to make such objects.

During its first decade of operation, Deerfield Academy instructors placed heavy emphasis on embroidery instruction. Jerusha Williams, preceptress from 1805-1812, was especially influential in this regard. Williams studied at Misses Pattens’ School where embroidered samplers and silk needlework that often featured biblical scenes were at the center of the young woman’s education. The needlework pictures made here are characterized by a “bright and crisp style,” featuring colorful silk threads and chenille on white silk backgrounds and highly raised and padded metallic embroidery that was often used to work an eagle holding a floral garland.[2]

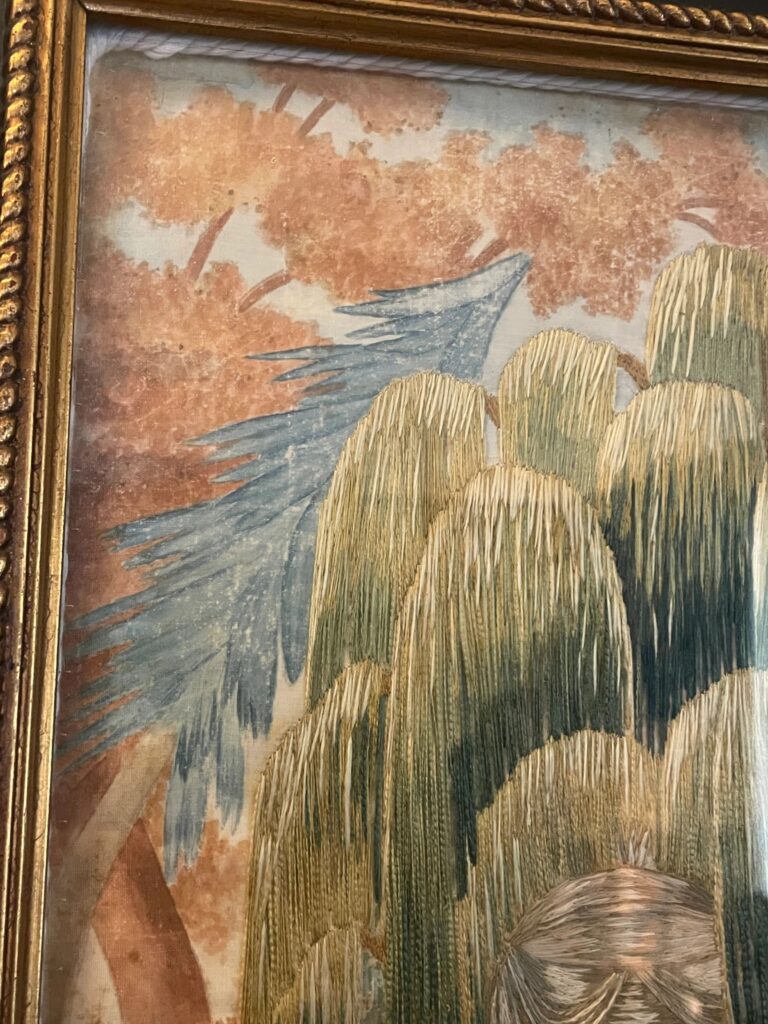

Williams brought these techniques and styles to Deerfield Academy, as evidenced in two pieces in the Historic Deerfield collections: a pole screen worked by Sarah Leavitt in 1810 and a needlework mourning picture made by Mary Upham around 1807. Leavitt’s pole screen is flush with styles and iconographies associated with the Patten School. Hovering in a graceful arch over the top of the composition are two glimmering eagles worked in gold thread and sequins that pop out of the white silk background, a garland strung between them united in the center by overlapping silver and gold hearts. And though more muted in color to fit the somber tone of a mourning picture, Upham’s needlework picture sets off the cornflower blue watercolor background—a hallmark of many Deerfield Academy compositions during this period—against varying textures of layered silk and chenille threads that bring the trees and grasses to life in a range of green and yellow hues.

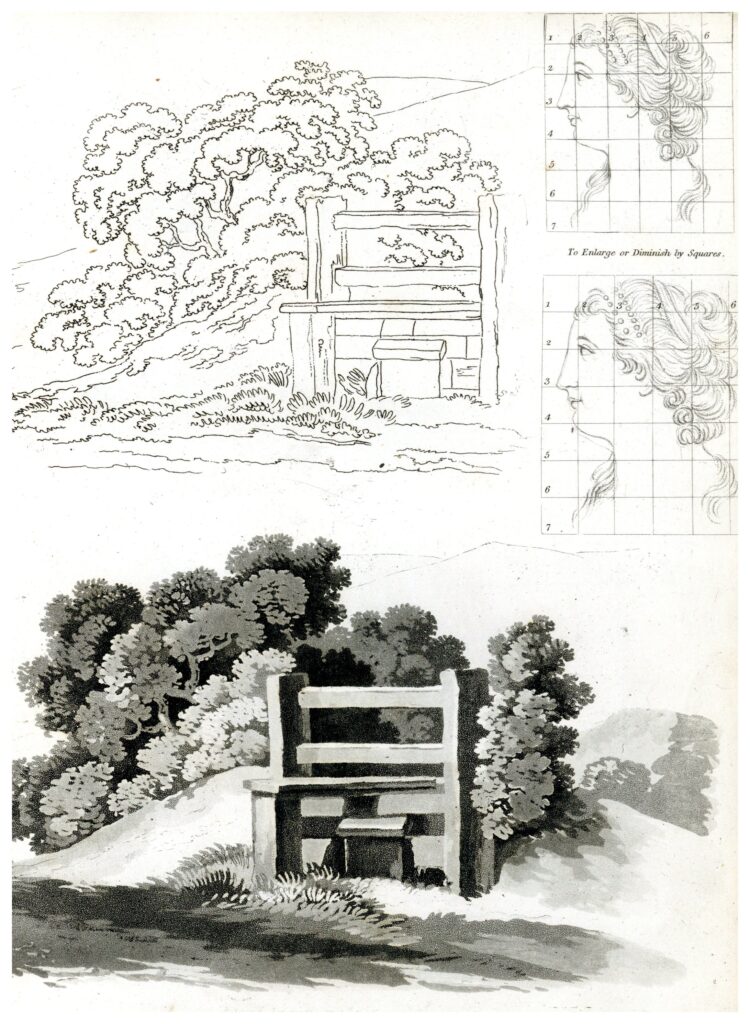

When Jerusha Williams left the Academy in 1812, Orra White Hitchcock assumed the role of preceptress, ushering in a new era for ornamental arts instruction at the school. Turning away from the detailed embroidery taught by her predecessor, White Hitchcock’s fine arts instruction emphasized drawing, watercolor painting, and cartography. She cultivated her students’ drawing and painting skills by having them copy portraits and landscape scenes in a distinct dappled stencil style from popular prints onto paper for beginning students, and, for the more advanced students, onto hand fire screens and wooden boxes. [3] Copying fashionable images was common practice at the time, taught by teachers like White Hitchcock and reinforced by the plethora of textbooks and instruction manuals marketed to young girls. Volumes such as The Young Women’s Companion, or, Frugal Housewife (1811) and The Cabinet of the Arts (1805) detailed directions and provided exemplary illustrations for drawing outlines and transferring, enlarging, or contracting source images.

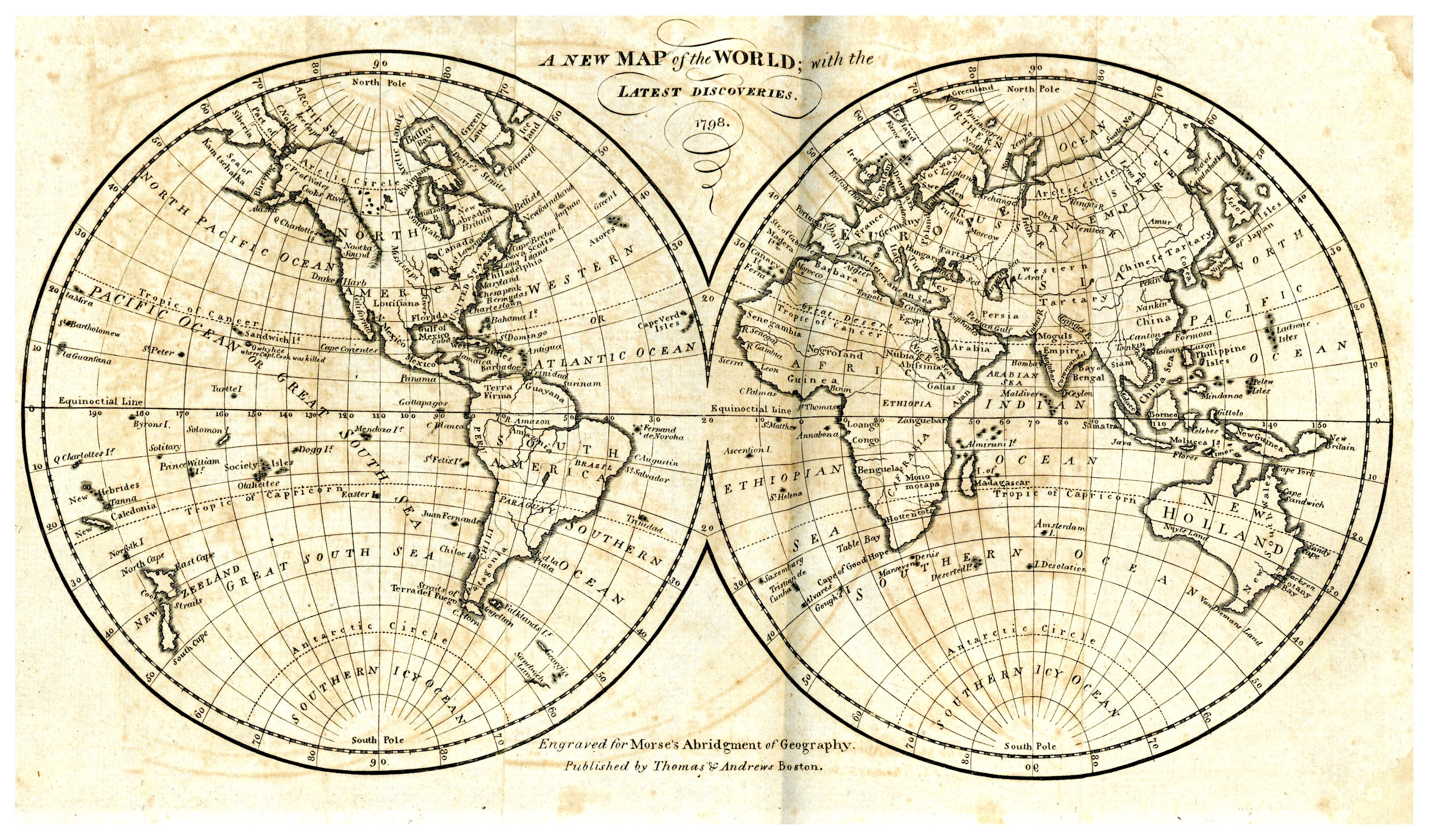

Learning to copy images was also at the heart of schoolgirl mapmaking. In an effort to help students master the principles of geography and cultivate ornamental art and penmanship skills, they were asked to replicate maps from mass-market atlases and geography and history textbooks. White Hitchcock likely learned the detailed art of mapmaking at Susanna Rowson’s Academy in Roxbury, MA. At Deerfield, White Hitchcock similarly taught her students to copy in ornate script and detailed outline engraved maps from Jedidiah Morse’s famed textbook Geography Made Easy (1798), producing large maps for display in the classroom or parlor walls at the students’ homes.

By copying illustrations, be they double hemisphere world maps, biblical and historical scenes, or landscape views, from popular visual culture sources through the techniques of their teachers, young girls at academies developed unique artistic styles. Rather than being a rote, non-artistic form of artistic reproduction, transforming an engraved print into a needlework or watercolor image in its likeness demanded technical experimentation and innovation. Tracing lineages of artistic techniques across institutional networks and instructor-student lineages at female academies, we can begin to tell the story of how gendered and racialized techniques shaped the aesthetics and circulation of popular visual culture in the early American Republic.

Allison Fulton is a Ph.D. candidate in the English Department at the University of California, Davis. As a recipient of a Memorial Libraries Research Fellowship, she spent 6 weeks with us in the fall of 2023 researching her dissertation “Disciplining Craft: The Gendered Making of Nineteenth-Century American Science.”

[1] Caryne Eskridge, “Sarah Hooker Leavitt’s Worktable: Women, Education, and Art Making,” Yale University Art Bulletin 2008, 62.

[2] Florence Griswald Museum, “Stitching It Together: Locations of Needlework Schools,” https://florencegriswoldmuseum.org/visit/families/stitching-it-together/locations-of-needlework-schools/

[3] Hand fire screens were small decorative objects used by women to protect their faces from the heat of a fire while simultaneously showing off their comportment and artistic talent (Suzanne L. Flynt, Ornamental and Useful Accomplishments: Schoolgirl Education and Deerfield Academy, 1800-1830 (Deerfield, Massachusetts: Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association and Deerfield Academy, 1988), 34. Many decorative objects made by White Hitchcock’s students are on display at the PVMA Memorial Hall Museum.