Shoes tell stories. They reflect the tastes of their owners, and reveal the wear and tear of daily life. Arguably, shoes receive more use than other items of clothing, offering challenges to their preservation in museums. This summer, I embarked on a project to rehouse Historic Deerfield’s shoe collection. Working in consultation with Kate Kearns, Collections Manager, and Ned Lazaro, Curator of Textiles, I designed and constructed storage mounts for individual shoes and pairs of shoes (Fig. 1). The mounts, custom fabricated out of archival materials, protect these fragile, historic objects while in storage and support the structure of the shoes to mitigate damage caused by their own weight. The mounts also serve to reduce future deterioration by allowing the shoes to be displayed and studied by researchers and students with a minimum of handling. Here, I report out on this preventative conservation project.

The Shoe Collection at Historic Deerfield

There are just over one hundred pairs of shoes in the collections at Historic Deerfield, spanning almost three centuries, from the early 18th to the mid-20th century. The footwear collection includes fashionable heels and flats from France and England, heels, slippers, and boots made in the United States throughout the 19th century and into the 1960s, and even a pair of Spanish children’s boots. The majority of the collection is composed of women’s shoes, but those worn by children and men are also represented.

Made from the delicate organic materials of textiles and leather, shoes rarely survive for centuries. Men’s shoes in particular were subjected to intense wear, which is one reason why the extant examples tend to be women’s or children’s shoes. Each shoe provides information about changing style preferences and manufacturing methods through time. This project was an intervention to drastically reimagine the storage plan for the shoes in order to maintain their continued longevity and historic value.

Mounting and Rehousing Footwear

When this project began, the shoes were housed in crowded storage cabinets. Many shoes were rubbing up against each other and some were on their sides (Fig. 2). Pairs could easily become separated. All shoes had to be handled anytime they were moved or studied. In addition to these protection concerns, many shoes were in need of conservation.

Our goal was to devise a mounting system for the shoes that would keep pairs together and organized on the shelves, provide structural support, and minimize the need to touch them when they need to be moved or studied. Drawing inspiration from similar projects undertaken by staff at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston [9] and The Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City [10], I devised a workflow to create custom mounts using archival-quality materials.

Conservation and Mount Construction

First, an appropriately sized corrugated archival board of ⅛ in.thickness was selected for the pair of shoes. A small handle of twill tape was hot-glued to the underside of the board, to aid in sliding the board forward to remove it from a shelf. Object numbers were written in pencil on the board.

The shoes rest upright on the board on a thin piece of Volara foam, measured and cut to the shape of the shoe’s footprint. Volara is a polyethylene, closed-cell foam often used for lining and padding to protect objects in storage. It is very soft and pliable, easy to cut with scissors. As a footprint, it provides a cushion and some friction to hold the shoe in place, without abrading the bottom.

Bumpers, constructed from thick strips of Volara, were glued onto the board, curving around the toe and heel of the shoes in order to secure them in place. With minimal contact, the footprints and the bumpers provide enough support to keep pairs of shoes upright during transport. Even if the board is held at a slight angle, the shoes will stay in place.

For shoes with heels or pronounced arches, I made shank support mounts over which the shoe would hook into place. These mounts were custom sculpted for each pair of shoes out of Ethafoam. Ethafoam is also a closed-cell polyethylene foam, but with a rigid structure. It can be cut to any shape and is often used to house historic artifacts.

I also provided interior reinforcements for each shoe, in the form of pillow inserts and mylar supports. Inserts were made from sewing cotton stockinette into the shape of the toe of each shoe and filling them with inert polyester batting. These inserts were custom designed for each shoe to provide adequate support to the toe box and vamp (the fabric that covers the top of the foot), while being inconspicuous when shoes are on view.

Mylar, an inert polyester film, was employed to support quarters (the rear part of a shoe), tongues, and boot shafts. Mylar is clear, allowing unobstructed visual access to shoe linings and insoles. Most shoes have mylar quarter supports, which are long strips cut to the dimensions of the shoe and placed inside. Shoes with large tongues received an extra mylar piece to prevent the tongue fabric from sagging. Boots, gaiters, and shoes with shafts received a long, rolled-up piece of mylar cut to the appropriate height that was inserted and then expanded.

The last shoe component that will be discussed are laces. For shoes with original laces at risk of getting tangled, or are too fragile to continue using as fastenings, I sewed cylindrical stockinette pillows around which the laces were wound. For shoes with missing laces, I used a blunt needle and thin string to lace up the shoes after installing a pillow insert into the toe of the shoe.

Rehousing the Shoes in Storage

Now, with each pair mounted on a dedicated board, no shoe is in contact with another and pairs cannot be separated. The object numbers can be easily read, and specific shoes removed on their boards without touching them or disturbing surrounding footwear. The commitment the museum has made for better shoe storage also means that the new mounts increase the amount of space needed to store the shoe collection, with each shoe mount’s “footprint” larger than the shoes themselves previously had (Fig. 2).

Footwear Case Studies

In this section, I will highlight a few specific pairs of shoes to demonstrate the range of the collections as well as conservation and mount construction strategies.

19th Century Slippers

This is a pair of women’s slippers made of dyed pink leather with linen lining and leather soles (Fig. 3). A rectangular label in one shoe reads, “PELATIAH REA’S / Variety Shoe Store, / NO. 2, Northwest corner of the old / State House, / BOSTON./ Rips mended gratis.” Pelatiah Rea (b. 1771) may have been the shoemaker or the shopkeeper who sold them. They have a rounded toe and very short vamp, suggesting a date of about 1810 [11].

These shoes received volara footprints and bumpers. I sewed pillow inserts to provide support to the toe box and to hold up the vamp and the latchet fastening. A matching pink ribbon had been previously added. Lastly, a mylar quarter support serves to hold up the sides and back of the shoes.

18th-Century Louis Heels

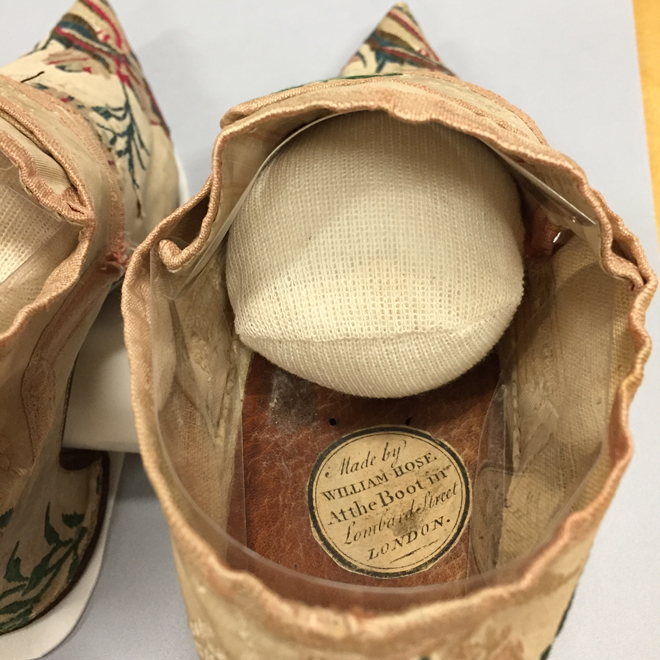

This pair of women’s heels were made in the United Kingdom around 1750 (Fig. 4). A round label on the insole of one of the shoes reads: “ Made by / WILLIAM HOSE / At the Boot in / Lombard Street / LONDON.” The shoes are made from a brocaded silk with a brightly colored floral pattern and pink silk tape. The Louis heel, popular in women’s shoes throughout the 18th century, is a wide and curved heel made of wood and completely covered in fabric [12]. The sole of the shoe is leather, uninterrupted from toe to heel, as is characteristic of the style. The interior is lined with plain linen. Each shoe has two overlapping straps over the tongue that would have been secured with a buckle.

When constructing the mount for these shoes, it was important that the interior label remain unobstructed. Additionally, as the design on the fabric around the pointed toe and heel extends down to the sole, no bumpers were used. This left the fragile brocaded fabric completely visible with no mounting materials coming into contact with the delicate exterior fabric of the shoe. It also makes the white rand, an important construction detail, visible. I sculpted a shank support mount that fit exactly under the curvature of the heels and cut out footprints for the heels and toes that matched the contours of the shoes. When glued down to the board, the footprints and shank support keep the heels from toppling during transport, from both friction and the curved heel hooking around the mount. For the inside of each shoe, I inserted a sewn, tapered pillow and added mylar tongue and quarter supports.

Child’s Laced Booties

This small pair of red leather booties were found in a chest of drawers in Historic Deerfield’s Allen House in 2011 (Fig. 5). Made for a child, these shoes have light brown twill weave cotton lining and some decorative embroidery. They were likely made in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. The shoes have some discoloration—evidence of water damage—and the leather was misshapen and brittle in some areas. One of the shoes could not stand up on its sole.

To support these shoes, I carefully reshaped them within the limits of the flexibility of the leather material. I sewed and inserted stockinette pillows, extending from the toe to heel to provide adequate structure support for these tiny shoes. After installing the pillow insert, I used black string to lace up the booties. I also added a cylinder of mylar into the shank of the booties. The stockinette pillow, laces, and mylar all work together to keep the shape of the shoe. They now stand upright on a small board with footprints and small bumpers.

I was able to construct mounts for 36 pairs of shoes over this summer. Through the process, I documented my work and wrote a step-by-step instruction manual so that museum staff may continue the work of preventively conserving and mounting the shoes. It is a labor-intensive project, but one which will greatly impact the longevity of the fragile shoe collection.

Danielle Raad was a Curatorial Intern at Historic Deerfield during the summer of 2019. She is a PhD student in Anthropology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This project was made possible by a Dr. Charles K. Hyde Public History Intern Fellowship from the Public History Program at UMass Amherst.

[1] Historic Deerfield 2001.43. Hall and Kate Peterson Fund for Minor Antiques.

[2] Historic Deerfield 2015.31. Museum Collections Fund.

[3] Historic Deerfield F.551.

[4] Historic Deerfield F.743.

[5] Historic Deerfield 60.264.

[6] Historic Deerfield V.062C, Gift of Mrs. James Erit.

[7] Historic Deerfield 2000.37, Hall and Kate Peterson Fund for Minor Antiques.

[8] Historic Deerfield 2001.36, John W. and Christiana G.P. Batdorf Fund.

[9] Gausch, Karen and Joel Thompson. “Conservation Project: Costume Accessories, Shoes and Footwear Photos.” Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 2019,

https://www.mfa.org/collections/conservation/feature_costumeaccessories_shoesandfootwearphotos

[10] Bacheller, Rebecca. “From Heel to Toe: The Costume Institute Shoe Rehousing Project.” Storage Techniques for Art Science & History Collections, 2014,

[11] Rexford, Nancy E. Women’s Shoes in America, 1795-1930. The Kent State University Press, 2000. Pg. 172.

[12] Ibid, Pp. 213-216.

[13] Historic Deerfield F.642.

[14] Historic Deerfield 2011.800.