By Ned Lazaro

Curator of Textiles

The depiction of flowers to decorate and embellish textiles has been an integral part of clothing for thousands of years. Where actual flowers wilt and die, realistic and stylized representations on fabric copying flower colors and shapes, and symbolizing life and renewed growth, survive. Mirroring a growing interest in plants and gardens, the appearance of flora on textiles likewise increased and diversified.[1] Eighteenth-century textiles worn for dress display some of the most elaborate and beautiful examples of flora, both real and stylized. Woven, embroidered, painted, and printed flowers depicted on clothing reveal the genre’s popularity. They delighted the eye, conjured faraway lands, and illustrated humankind’s attempts to harness fleeting beauty onto the human form.

Woven Flora

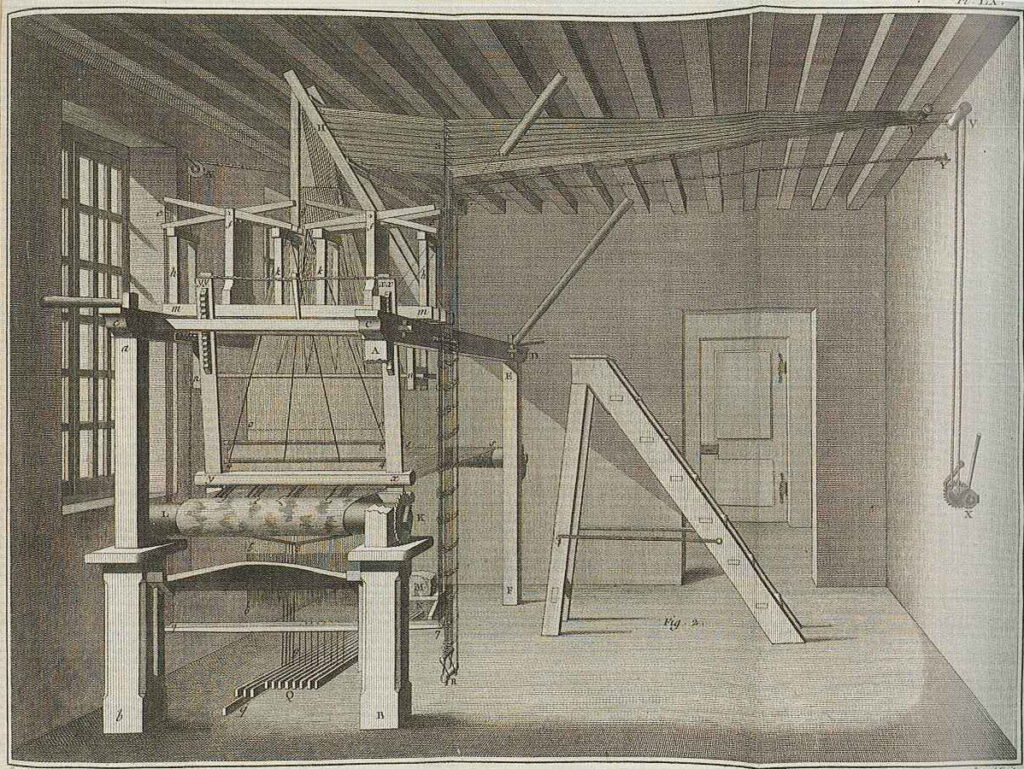

The eighteenth century’s drawloom allowed for unparalleled and realistic representations of flowers in woven textiles (Fig. 1). Floral patterns were first drawn out by specialized designers who found inspiration in nature, gardens, and the work of other artists. Some also received academic training.[2] Successful designers had an understanding of what was possible for master weavers to create using a complicated loom that bound warp and weft threads in a myriad of ways.

These artists also paid attention to fashion, usually emanating from France, with current trends and the relentless desire for novelty leading the way. One such trend began in the 1730s. At that time, French and English weavers began depicting flowers more realistically. Artistic improvements in the weaving of brocaded silks created an effect known in French as points rentrés, adding shading, and therefore depth, to flowers, buds, and fruit (Fig. 2a, b) by interlocking brocading threads.[3] Motifs grew considerably in size as the vogue for more detailed and lifelike flowers became possible. Large, asymmetrically repeating motifs, as well as secondary or background designs, also created the illusion of realism, echoing the imperfections of nature. The inclusion of metallic thread further heightened the allure of these flowers (Fig. 3a, b). When new, these untarnished metallic elements reflected candlelight in the evening, illuminating dark interiors and captivated onlookers.

Embroidered Flora

Embroidery is the process of using a needle to add design to an already-woven fabric or other ground (such as leather). Embroidery was uniquely suited to represent flowers in the eighteenth century; a needle and thread could easily create small, detailed motifs in ways ordinary weaving could not achieve (Fig. 4). Embroidery also allowed for a higher degree of individualization in designs not possible with weaving (Fig. 5a-c).

Like weaving, formal instruction in embroidery guilds in England and France was almost exclusively for men. However, women had the chance to embellish their appearance, and that of a loved one, through embroidery done in more informal settings such as the home, or taught as an ornamental art at a school. The mastery of stitches could later serve as a creative outlet for some women to embellish items of clothing such as petticoat hems (Fig. 6). Regardless of the context of training, skilled embroidery and a variety of stitches created nuanced shading and texture that added to a floral motif’s lifelike qualities.

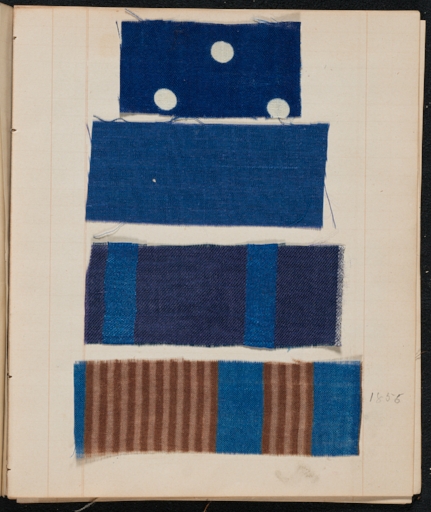

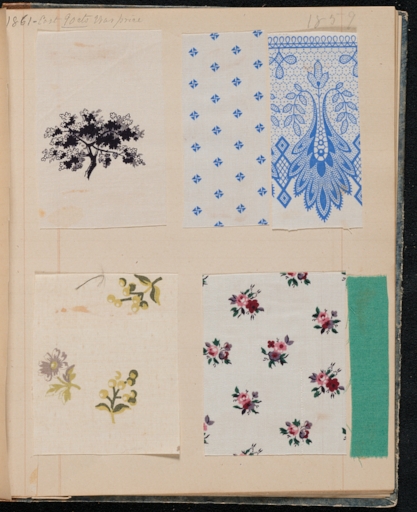

Painted and Printed Flora

Seventeenth-century Indian painted-and-printed cottons captured the interests and imaginations of England and Europe. The finest examples of chintz trumpeted the skill of Indian artisans, especially those from the southeast Coromandel Coast, who used a combination of mordant- and resist-dyeing techniques on mostly plain-woven cotton fabrics to create detailed and colorfast designs.[4] Enterprising people in the West soon sent designs, or musters, to these Indian craftsmen to copy in the hopes of better appealing to customer tastes back home. Besides colorfast designs, the ability of these Indian artisans to create patterned fabric featuring white, undecorated grounds to set off vibrantly hued motifs only increased their vogue in the West (Fig.7a, b).

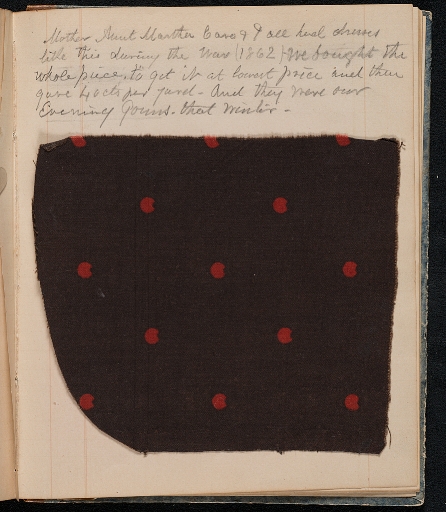

By the early eighteenth century, long frustrated by their lack of success replicating the colorfast techniques of India, English and European printers and dyers began experimenting in earnest (Fig. 8). These efforts eventually yielded more generalized, less detailed designs using printing techniques. Writing about his late eighteenth-century childhood during the 1840s, Deerfield, Massachusetts, historian Epaphras Hoyt (1765-1850) remembered women in the 1770s wearing “calicos [of] stamped linen” when more popular printed cottons imported from English merchants became unavailable during the American Revolution. Hoyt recalled these homemade versions possessed motifs created by using wooden stamps that decorated the linen with motifs that “might please the eye.” But the colors achieved, using inferior, natural dyes that were locally available, did not last.[5] By the end of the eighteenth century, however, these experiments paid off. Woodblocks, engraved copper plates, and cylinders were all employed to produce stylized floral designs, which also became smaller as the century ended (Fig.9a, b).

In addition to their pleasing, decorative effects, the inclusion of two-dimensional flowers on textiles worn for dress on three-dimensional bodies held deeper meanings in Western society. Flowers could spark conversation and interest. New or exotic flora could signal knowledge of the latest trends in horticulture or an awareness of different cultures.[6] In this way, these fabrics served as portable libraries or communicators of a person’s knowledge, as well as reflect their access to, and knowledge of, the latest fashions.

[1] Vanessa Remington, Painting Paradise: The Art of the Garden (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2015).

[2] Lesley Ellis Miller, “Education and the Silk Designer: A Model for Success?,” in Mary Schoeser and Christine Boydell, eds., Disentangling Textiles: Techniques for the Study of Designed Objects (London: Middlesex University Press, 2002), 185-194. Moira Thunder, “Improving Design for Woven Silk: The Contribution of William Shipley’s School and the Society of Arts,” Journal of Design History 17 No. 1 (2004): 5-27.

[3] Lesley Ellis Miller, “Jean Revel: Silk Designer, Fine Artist, or Entrepreneur?,” Journal of Design History 8 No. 2 (1995): 79-96.

[4] Rosemary Crill, Chintz: Indian Textiles for the West (London: V&A Publishing, 2008).

[5] Epaphras Hoyt, “Dress of Females,” in Recollections of times and things of my early life, with a sketch of recent improvements, and remarks upon the principles of our government, on our parties & our frequent political condition (unpublished manuscript), 25. Historic Deerfield Library. Thanks to Barbara Mathews, Public Historian and Director of Academic Programs at Historic Deerfield, for bringing this to my attention.

[6] Clare Browne, “The Influence of Botanical Sources on early 18th-Century English Silk Design,” in 18th-Century Silks: The Industries of England and Northern Europe (Riggisberg; Abegg-Stiftung, 2000), 25-38.