by Morgan Brennan, Curatorial Intern

Fig 2. Waistcoat F.510 held up (center left)

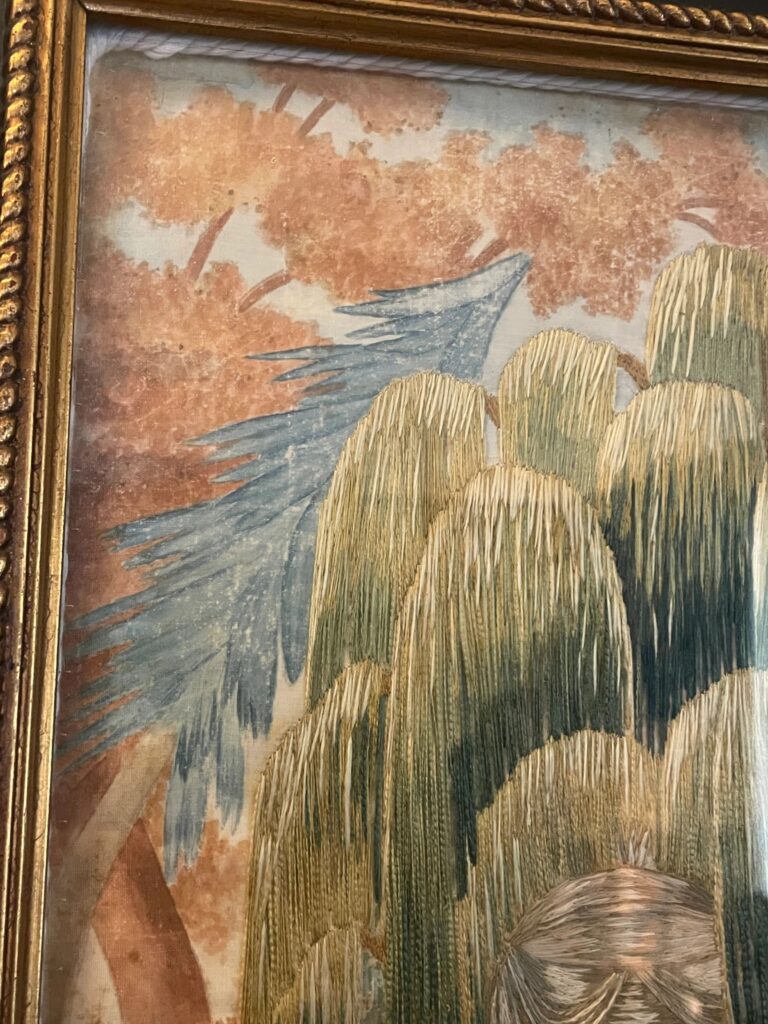

Fig 3. Persian Silk Tree embroidered detail (center right)

Fig 4. Image of a Persian Silk Tree (right)

A waistcoat in Historic Deerfield’s collection (accession number F.510) is just one of over 8,000 items that comprise the museum’s collection of textiles and historic fabrics. The waistcoat is made of a cream silk, decorated with Chinese embroidery of plants and a variety of birds. The designs on these incredibly fine embroideries were often inspired by real plants and animals, such as the Ring-necked Pheasant and the Persian silk tree. However, on the whole these flora and fauna are decorative, not scientific, and like their European painted counterparts they tend towards being composites of various plants or several species of bird at once. [1]

This embroidered fabric was used to make the first iteration of the waistcoat we see today. In the eighteenth century, English and European men’s waistcoats were made of richly decorated fabrics, especially fabrics brought in from China or France, which reflected the wearer’s wealth, taste, and cultural savvy. These fabrics were expensive and thus used primarily on the exterior of the garment, with an inner lining most often made of fine linen to protect the expensive outer fabrics from the wearer’s sweat and skin oils.

Fig 6. Scientific drawing of a Ring-necked Pheasant (center)

Fig 7. Photograph of a Ring-necked Pheasant (right)

Fig 9. Crested Goshawk photograph (center)

Fig 10. Crested Goshawk photograph (right)

Fig 12. Gambel’s quail photograph (center)

Fig 13. Button quail photograph (right)

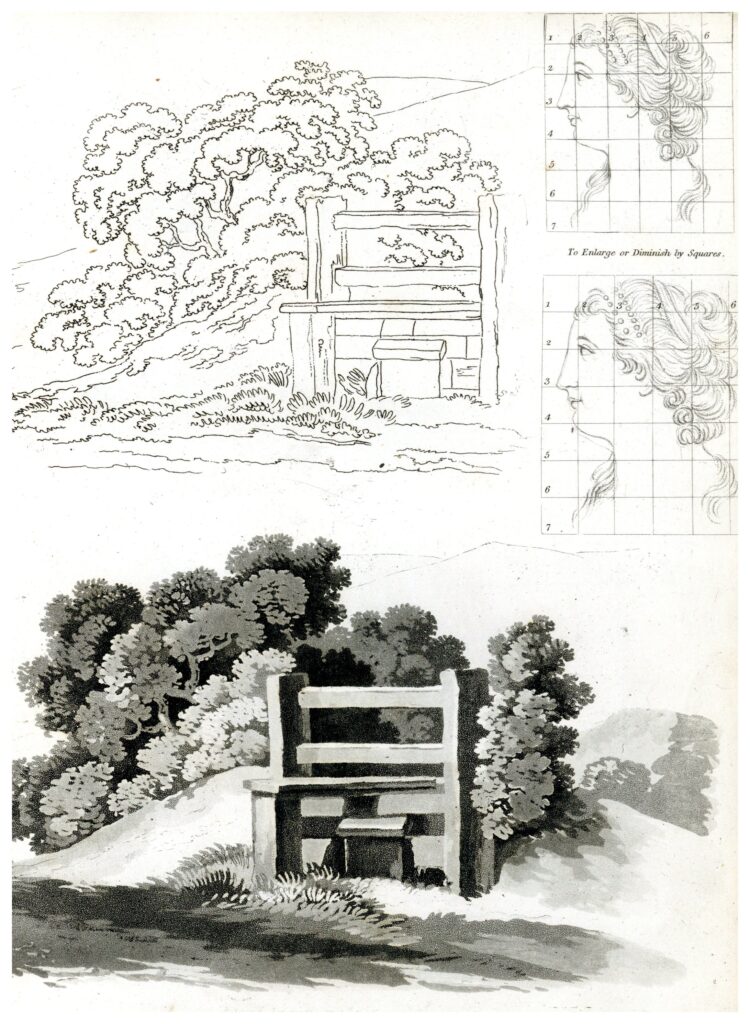

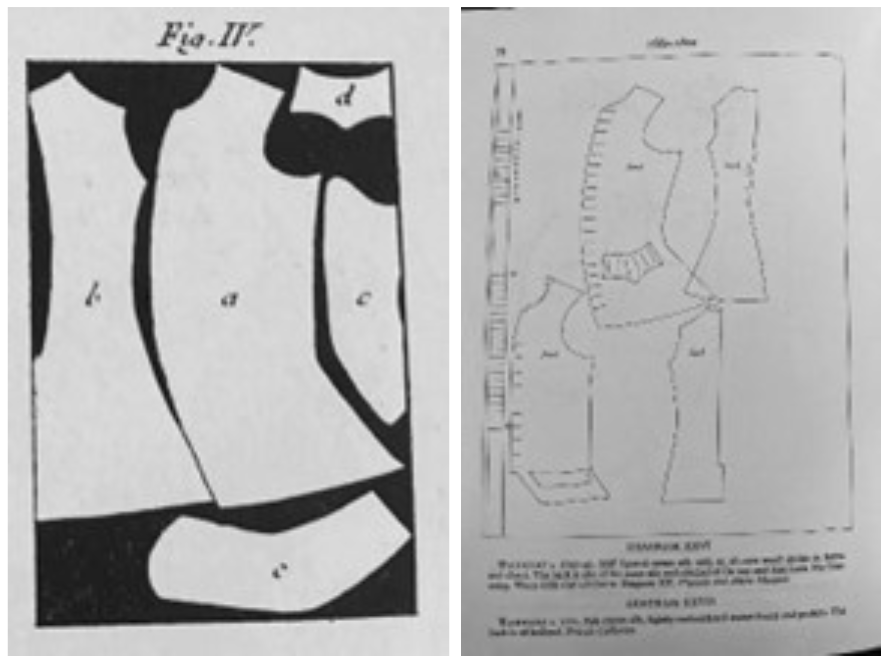

The original man’s waistcoat was made in England or Europe around 1780. Earlier examples of embroidered waistcoats in the 1700s are longer with the pockets scalloped, and the bottom of the garment cut in a “V” shape below the final button. Later examples in the 1790s were increasingly rectangular, with rectangular faux pockets, and without an angle below the lowest button. The density of embroidery near the buttons and in the space between the pockets and hemline is also a distinctive marker of this era. [2]

Fig 15. Silk waistcoats of the mid 1700s, p. 78 (right)

The waistcoat seen now has been significantly altered to fit a woman’s form. The shape is reminiscent of the 1870s “princess line” style in western European women’s fashion, but the dropped bust suggests a later date of alteration, perhaps closer to 1900.

A similar waistcoat in Historic Deerfield’s collection (accession number F.730) was altered for a woman’s figure around the same time frame as F.510. The fabric for F.730 is estimated to be from around 1770 and to be of English or French origin. The alteration is estimated to be circa 1785 and then again around 1880–1920. F.730 is also a cream white silk and plain weave linen with polychrome embroidery on the silk.

The curatorial file for F.730 posits, “Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition of 1876 sparked nostalgia for 18th-century customs, including dress. Those people who had access to actual period garments often altered them into ‘fancy dress’ clothes that modern bodies could wear to Colonial Revival-themed events. This example, originally an item of menswear, was altered to fit a woman. Darts at the waist provide the fit required by fashion for women at the turn of the 20th century, more than 100 years after the garment’s original life.” [3] With this in mind, F.510 might have been among the garments altered in the colonial revival era, following the timeline of F.730 with its 1880–1920 alteration date.

Fitting the F.510 waistcoat to a female form took a great deal of work. The back was let out with a triangle of linen. Then, the waistcoat was carefully shaped to the contours of a woman’s body, taking in the fabric in three places to emphasize the slimness of the waist, including in the front of the garment where a dart shows where the fabric was taken in. A piece of boning was put in near the buttonholes to keep the front of the garment lying flat on the body.

Inside of the garment, the shape of a silk embroidered panel shows how the outward collar embroidery on the men’s version was turned inward to create a higher, round-necked silhouette. On the sides of the garment, there are two matching holes, likely the insertion points for a belt or matching ribbon of some sort, which would have helped emphasize the shape of the garment when worn.

The pocket flaps are interesting and possess some of the densest embroidery in the piece. Upon closer inspection, the pockets are simply pieces of densely embroidered fabric stitched onto the garment after it had been reshaped. The collar too is made of this same densely embroidered strip and is not the original collar embroidery. These pieces might have been taken from the original men’s garment when it was shortened around 1880–1920 to accommodate prevailing fashion trends. A line of stitch work running just under the faux pockets suggest a full cut and then shortening of the waistcoat to preserve the original densely embroidery bottom of the garment, which would have resulted in strips of excess embroidered fabric, some of which was used for the faux pockets and the collar additions.

In 1965, the F.510 women’s waistcoat was sold by the Parisian dealer Madame Niclausse. This French company was led by two women, Mme A. Niclausse, for whom the business is named, and Juliette Niclausse, who was an art historian and biographer. The waistcoat was sold to Henry Flynt, co-founder of Historic Deerfield, along with seven other Niclausse objects over the course of a decade. [4] Henry’s wife, Helen Geier Flynt, was an enthusiastic collector of fine French and Chinese textiles from the eighteenth century.

It is likely that a number of altered waistcoat examples exist in the collections of other museums. Unfortunately, these objects can be hard to find because of confusion over vest, waistcoat, and jacket labels and the tendency for alterations to garments to go unremarked upon in museum catalogue descriptions. The Fashion Institute of Technology’s “Fashion Unraveled” exhibition in 2018 focused on mended, altered, and repurposed garments. [5] However, altered garments are not just the purview of museum collections. Clothing alteration today, even something as simple as taking in a hemline, is a continuation of the long practice of people changing their clothes to suit new purposes.

Fig 18. F.510 inside panel (center left)

Fig 19. F.510 side detail with belt hole (center)

Fig 20. F.510 collar detail Fig 21. Waistcoat (center right)

Fig. 21 F.510, prepped for storage (right)

Special thanks to Lauren Whitley, Historic Deerfield’s Curator of Clothing and Historic Textiles, for her help in untangling the history of this piece.

[1] Milton M. Klein, ed. Historic Deerfield F.510 object file.

[2] Norah Waugh, The Cut of Men’s Clothes, 1600-1900 (Faber & Faber, 1964), 78, 95.

[3] Historic Deerfield F.730 object file.

[4] Historic Deerfield Niclausse dealer’s file.

[5] Colleen Hill, Fashion Unraveled, Until November 2018, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York City. https://www.fitnyc.edu/museum/exhibitions/fashion-unraveled.php.